Towards an Objective Reality

To Plato, who told me to write about what I think.

To Nietzsche, who told me to get weird with it.

~

The subjective is, quite frankly, a drag.

Not only can we never truly validate our beliefs, we’re often unaware of what beliefs we even hold. What we consider a philosophy can often be described as a psychological condition.

Take the idea of virtue and compare it to obsessive-compulsive disorder.

We can break virtue into two components: virtuous character and virtuous action.

Virtuous character is ‘knowing right.’ The more we try to be a good person, the more every decision we encounter becomes a moral dilemma - which is the good choice, and which is the bad choice?

We become obsessed with ‘being good’ because we have invested so much energy in building this identity, this context in which we are a ‘good person’, and it all falls apart if we make or start making ‘bad decisions’.

Whenever we are confronted with a negative reality of ourselves, it produces a deeply unpleasant physiological sensation called cringe. We hate feeling cringe (well, most of us) and become afraid of experiencing it.

This cringe-anxiety keeps generating moral dilemma after dilemma for us to overcome in order to keep delaying that confrontation. In everything, we start to see a moral choice to be made to validate our good character. We become obsessed.

Virtuous action, on the other hand, is the compulsion. This is the set of behaviors (even empty rituals) we perform to soothe this cringe-anxiety. When we start to ask ourselves if we’re only performing good deeds for social validation, the entire system of virtue becomes almost too difficult to bear!

We prescribe a cognitive treatment called “moral art” – the mental practice of connecting your actions back to your character, in order to get the most mileage out of your good deeds (read: obsess less). A competent practitioner may also perceive as less painful the sacrifice required for the action, like giving up meat.

If you try to withstand the compulsion, you become aware that you are an ivory tower: all theory, no praxis. You start to wonder if dogmatism is good, since it lowers the barrier to praxis, as black bloc anarchists demonstrate. You do not let yourself feel good without virtuous action; you tell yourself, ‘That’s what the fascists did!’ Your agitation becomes unbearable.

Just like obsessive thoughts, your ‘good character’ only exists in your head. In reality, we only consider the action to be virtuous, since we all know that good actions (like paying taxes) can be performed by people with bad character.

Yes, what philosophers call virtue ethics is what psychologists call OCD.

In addition to compulsion, how many of our ideals are not simply intellectualization (a psychological defense mechanism)? “I enjoy watching reality TV because it’s an anthropological study.” No - if you wanted an anthropological study, you’d read a paper; you just want to watch trashy TV. You can admit it! You’re among friends here.

We know not what we believe

A Marxist rebuttal to rationalism involves historical materialism - that our values are a product of the material conditions in which we were raised. Well, just like those obtuse rationalists, activists are unaware of the role their material conditions played in determining what they so ardently call a “just cause” - a universal mandate. In fact, nobody pays attention to their own material conditions when arguing a universal principle - they are two incompatible contexts.

And since the activist is not in the context which uses historical materialism to explain their own views, they are missing the tool that explains why they hold their position. Thus, they are not aware of why they believe what they do.

We also treat our beliefs as if they are fixed. We do not give them space to move and evolve. But the framework for our beliefs, our mind, is constantly changing!

When I was young, I could not visualize one trillion. Now that I am older, I can. Take ten cubes along the x-axis, then ten cubes along the y-axis, and then ten along the z-axis. Here, you have a cube containing one thousand. Simply repeat the same exercise and you have one trillion.

The limit of our comprehension is constantly changing (growing in some places, shrinking in others…) Why should we try to keep our beliefs stationary?

In light of this, we display wisdom when we admit that we do not know something and that the appropriate time to learn it will come later.

Therapists share this perspective, and chase after their patients’ rhetorical questions like shiny objects. To paraphrase Freud: we are constantly saying one thing and meaning a mother.

Honorable mentions:

- Republicans who denounce socialism unless it’s the military

- Utilitarians who ‘don’t care about the economy’

It’s dangerous to be unaware of what you believe. Going through life this way is like speeding: no harm comes from it, until it does.

You can see why I say the subjective sucks. Unlike a board game, you will never receive validation for your beliefs.

Appearances can be deceiving

Plastic surgery- Our tolerant culture will say there is no difference between undetectable plastic surgery (justified belief) and the genuine article (knowledge). Yes, botched surgery gets under our skin, so to speak, but this illustrates how highly we value it when done well.

Social issues- We observe, during periods of social justice agitation, the anti-dogma crowd is silent, paralyzed by indecision in their ivory tower, and we take their inaction to mean they are complicit, and part of ‘the right’. See: criticism of the few respectable IDW members who side-step talking about race.

Art- tricks you into thinking the imaginary real.

The manner through which we are deceived is our aesthetics.

Our aesthetics are a set of ideals that control how natural phenomena are subjectively experienced. The process of experience creates a subjective phenomenon called feeling.

We hold these aesthetics as ideals, but access them through symbols. We turn natural phenomena into a collection of comprehensible symbols, like how a compiler turns written code into a collection of tokens. We experience everything symbolically.

In other words, symbols are physical manifestations of aesthetic ideals.

Symbols are most powerful when they’re attached to people. A person’s skin color, manner of dress, height, etc. mean far more to us than seeing a sign on a laundromat, or the color of a Toyota, or a baseball stadium. This is why White liberals are so proud that our VP pick is Black, female, and Southeast Asian: these symbols have real power!

I will have more to say on the origin and properties of aesthetics in another paper, but I want to call your attention for a moment to feelings.

Feelings enable us to practice self-deception. We can make ourselves feel good about things. We can make ourselves feel bad about things. And we all know that which feels bad may end up being good.

‘So, what good are feelings?’ you may think I’ll ask – but no. Feelings are crucial to reality. Ben Shapiro may say facts don’t care about feelings. That you have a right to be safe, not a right to feel safe. But what is the value of safety without the feeling of safety?

Reclaiming objectivity

At any rate, we’re stuck with the subjective. But are we stuck in its basement chained to the radiator with moral relativism?

There is no shortage of self-help gurus who say no. (Unfortunately, I am one of them.) They are a creepy bunch, who withhold their ideas from academia where they would face certain death under the microscope of peer review.

A psychiatrist named David Hawkins has, for example, created a metaphysical Dewey Decimal System, where every philosopher has a ‘calibration’:

| 700-1000 | Enlightenment |

| 600 | Peace |

| 500 | Love |

| 400 | Reason |

| 350 | Acceptance |

| 200 | Courage |

| 100 | Fear |

| 50 | Apathy |

Plato comes in at 490. Poor Marx only 130. And Bob Dylan beats ‘em both at 500.

America is 415, Europe is in the 300s, and the scale itself is 605.

What nonsense! Ideas like these are snake oil: what is claimed to treat everything treats nothing.

And don’t get me started on Jordan Peterson. He blames the preponderance of moral relativism on ‘Postmodernism’ - an idea he thinks means “hold something as true if the ends are justified” – e.g., saying transwomen are women. And how does he combat this ‘postmodernism’? By embracing Christianity because it gives us a better moral and epistemological framework. How thoroughly hypocritical.

My goal here is to reject relativism. Not just moral relativism with its female genital mutilation and Qatari slave labor, but metaphysical relativism, too. (For its a short jump from “who says crystals don’t have energy” to “maybe vaccines do cause autism”.) And even beyond metaphysical relativism: to reject relativism as a state of mind, a desire to go with the flow, to stop resisting, to become one with the universe instead of one in the universe.

I want to answer questions like, are we more than the sum of our parts? Do we have free will, for if we don’t what is the point of consciousness in a deterministic universe? Is determinism real, or just something that feels justified in retrospect? Can people truly change who they are, for if not what is the point of moral philosophy?

Very well. Let’s give it a shot, this attempt to climb back into the objective. Only, we’ll need a new name for it. Say goodbye to the old objective - it is gone! Push it out to sea and give it a Viking’s funeral.

What we want is the neo-objective.

Functions

Let’s start by examining language.

Language is, in effect, a conscious or unconscious filtering of natural phenomena through the lens of our experience and opinion. More than that, language is the set of rules by which this channeling takes place. In some cases, objects are gendered; in other cases, there is no concept of time (see: linguistic determinism).

So if I experience X and I call it Y, language is the function through which X passes to become Y.

What else acts as a function? Aesthetics.

The process through which we transform the objective into the subjective, aesthetics, takes a thing and makes it a pretty thing or a good thing or a bad thing.

Remember: aesthetics are not only positive. We observe in psychology that our impulse away from is stronger than our impulse towards - see: people whose entire existence is centered around avoiding death or discomfort.

So, aesthetics is a function that turns objective into subjective.

Language is a function that turns subjective into subjective.

What is a function that turns subjective into objective?

Here was my giveaway:

When I talk about ‘will’ and you talk about ‘will’, they are the same idea.

We can reject that they are different ideas because, if they were, nobody would have any idea what anyone else means. But, clearly, we do. When Nietzsche talks about the will, or any idée fixe, we are all following along. Ideas are (at least when correctly expressed) universally understood, and as such we can call them unique.

Now, let’s step back a moment.

If ideas are unique, there must exist a context which guarantees their uniqueness.

This is a conclusion we’ve drawn purely through reason. We cannot experience or even perceive this context because it is the integral of an idea, and ideas are as high as our brains go. (Asking yourself what the ‘integral’ of a thing would look like is a useful exercise.)

What we have just done is ascertained knowledge about something objective indirectly. I admit we must hold the position that there is a consistent logic to objective reality… but without this position, you can only be an absurdist. This is one of those happy papers where we create our own meaning, even if it is merely global instead of universal.

Neo-objectivity toolkit

That little exercise we just did - that let us grasp at objectivity - let’s call that a tool (the integral method) and put it in our toolkit.

Remember: we are saving the tools themselves, not the conclusions we draw (though they may appear later in dubious arguments.)

What else is in this toolkit? Here’s another useful one.

As I said earlier, we are often not aware of our beliefs. So let’s try a game. Let’s say you think you believe in materialism: that the mind is the brain and that’s the end of it.

Okay, we’ve established that for you, mind = brain. Let’s try substituting one for the other in phrases or contexts:

- Mind your business becomes ‘brain your business’,

- ‘He has a mind tumor’,

- ‘Brain over matter’

Clearly, in your head, the mind is not the brain. Let’s call this method of inquiry the substitution method, and we will use it more shortly.

But first, I want to talk about contexts.

Contexts

Let’s explore essentialism using the toolkit so far.

My dog has several identities. She is “Pancake”, she is “a pet”, and she is “an animal”.

Essentialists would say these are all just describing the same thing, and that we are just playing a “language game”.

But we are not. Observe, using the substitution method.

- I would not spend $10,000 for an animal.

- I did not buy her at the Pancake store.

- The jungle is not full of Pancakes.

We have established that the identities “Pancake”, “a pet”, and “an animal” are in some way materially distinct.

Furthermore, these identities cannot exist at the same time!

She’s either “Pancake” or “an animal” (as least as far as reasoning goes; I may experience all three during my ‘symbolic experience’ of her.)

Let’s say that each of these identities represents a different context.

Do you feel the inertia when you move between contexts? This code-switching fatigue?

When I hold the “Pancake” context, I figure out certain things: what I would do for her, how I want to treat her, how much time I want to spend with her - I create a whole set of moral values based on her being “Pancake”. That takes work! It’s no easy task to build out a context, which is why people can only handle a certain number of contexts. Drunk people can often only sustain one.

For me to switch between contexts, there is context-associated data I must recall. Things I’ve figured out before. My point is: switching costs energy, and we develop an inertia against it.

Similarly, we frequently train our minds to favor a certain context. A predilection to interpret experiences this way rather than that. Example: people who come to enjoy and prefer suffering (the martyr types). They come to experience failure as cathartic: a deep back-scratching for the knots in our brain. (Or was it our mind?)

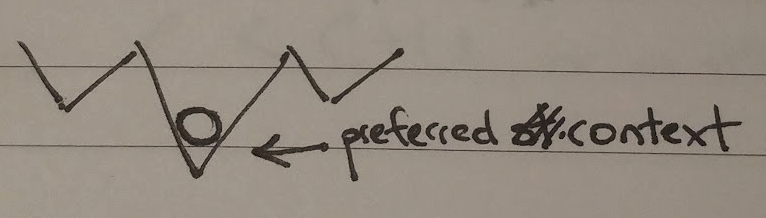

We prefer the contexts in which we’ve invested the most.

In summary, each identity we identified through the substitution method belongs to its own context, and a context is a distinct set of identities and derived data for the purpose of evaluating possibilities of a dilemma.

Knowledge conditions

I’ll give you a third tool, called knowledge conditions.

Let’s look at a dilemma we might ask: are there infinite parallel universes, or just one?

First, let’s look at the one-universe possibility:

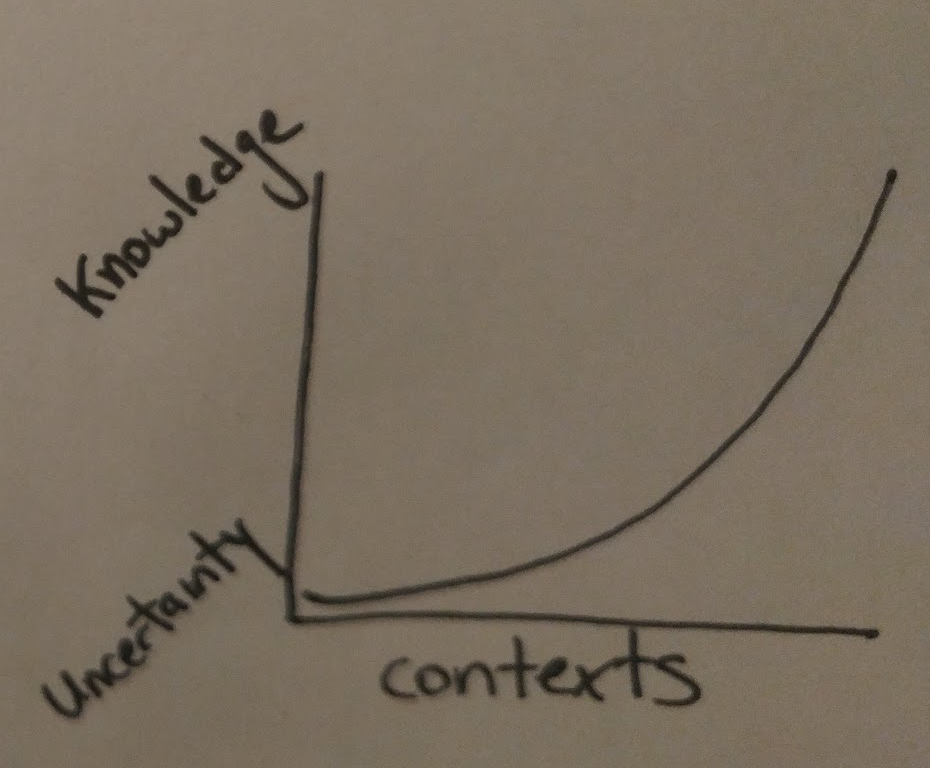

When investigating a phenomenon (an event), there is a set of possible causes (m) and possible effects (n). We’ll say knowledge occurs when we connect causes to effects (m/n).

Furthermore, we stipulate that for every cause there is an effect, and every effect has a cause.

Also, let us reject the premise that there are supernatural phenomena. As scientists, we believe that all natural phenomena can be (eventually) explained. In other words, there are no inconceivable effects.

But we do not hold causes to this same standard. When looking for causes, in addition to what we can conceive, we allow that there will always be causes that we will never understand, like what causes a psychotic break. We cannot know the mind of a madman.

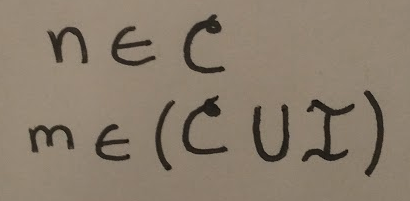

Thus, while n belongs to the domain of conceivable ideas (C), m belongs to the union of conceivable and inconceivable (I)

This is good, since it means frequently m > n: When the number of possible causes is larger than the number of possible effects (m > n), we find that we tends towards knowledge, or that we have a “favorable” knowledge condition:

Let me explain:

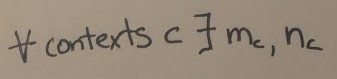

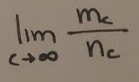

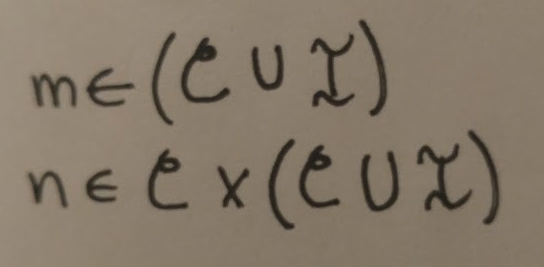

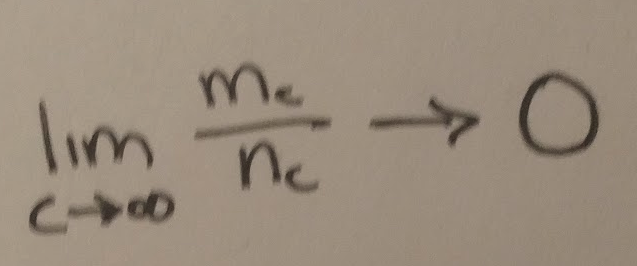

Let’s say that for a given context, or way of perceiving the event, c, we have mc and nc, where mc is the total number of possible causes and nc is the total number of possible effects in that context.

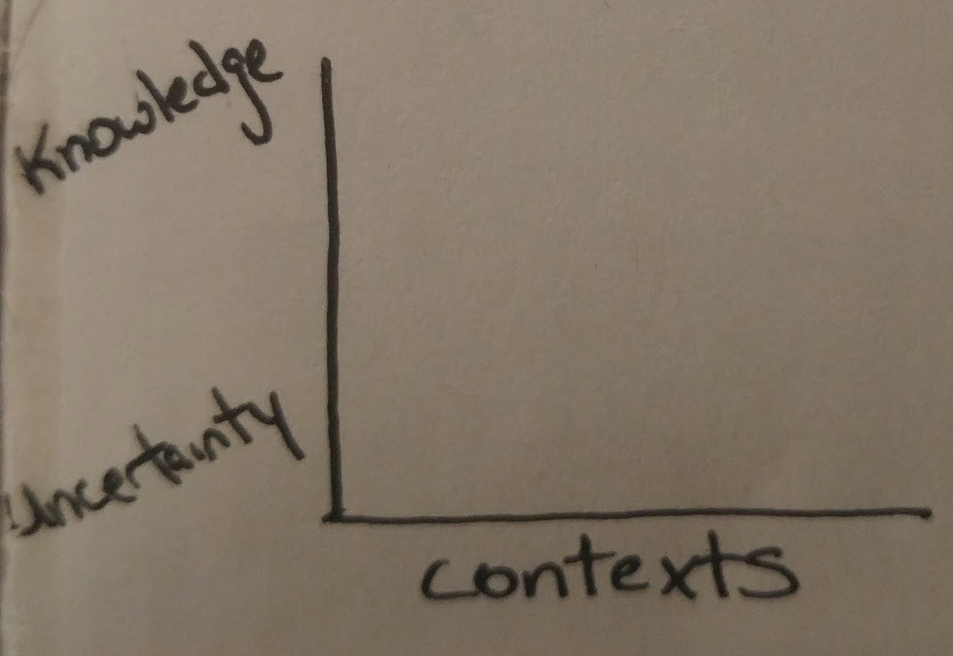

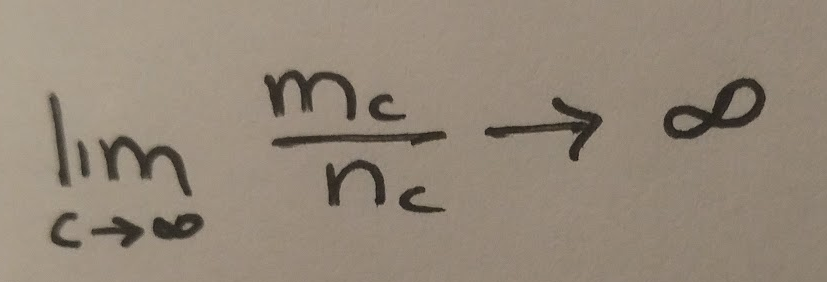

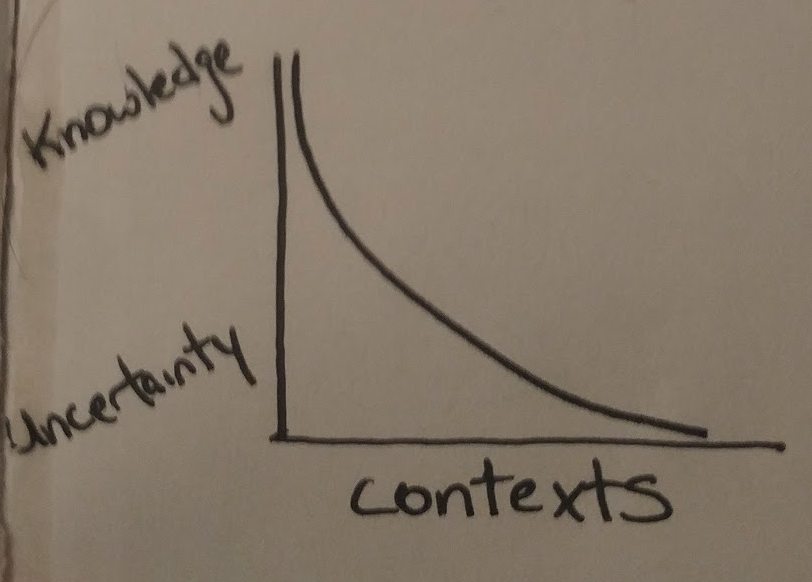

We create a graph that looks like this:

We ask, what is the limit of knowledge (m/n) with respect to context?

Well, when mc > nc for generally all contexts c,

Thus, our graph becomes…

In plain english, a possibility in which there are more causes than effects is one that tends towards knowledge.

Now, let’s look at the infinite universe possibility.

We no longer hold the lemma that for every cause there is an effect. In this possibility, for every cause, there could be any conceivable outcome. If a butterfly flaps its wings, there exists a universe in which Mars self-detonates.

This flips the equation (m < n), and we notice that the number of effects outpaces the number of causes.

Giving us the graph…

Such a possibility throws phenomena at us faster than we can explain them.

When approaching this dilemma, we do not engage with the idea directly since we cannot conceive of it, but instead we can observe the red-shift in its knowledge conditions: whether it is converging on uncertainty, or accelerating towards knowledge. I call this phenomenon the Doppler Effect.

At this point:

We have defined 3 functions.

We have 3 tools in our toolkit.

We have just inquired about the limit of knowledge with respect to context.

We have identified that of the two possibilities in our dilemma, one has a favorable knowledge condition and one has an unfavorable knowledge condition.

Neo-objectivity

Let us finally define neo-objective reality:

That which is a) unknowable through direct inquiry, and b) knowable using the tools in our neo-objectivity toolkit.

The ‘infinite universes’ possibility, which has a knowledge condition that tends towards uncertainty, is unknowable and is therefore not part of neo-objective reality.

In other words we say that in neo-objective reality, there are not infinite universes.

Putting it all together:

- We have used the integral method to show that ideas are unique.

- We have used the substitution method to show that ideas are materially different, and postulated that each distinct idea has its own context. The substitution method also gave us a way to identify contexts.

- We took the integral of knowledge with respect to context to determine knowledge conditions.

- We say that one possibility of a dilemma either tends towards knowledge or uncertainty.

- Based on the criteria of neo-objective reality, we reject possibilities that are intrinsically uncertain (unknowable), and begin to paint a picture of what neo-objective reality is.

Advice to neo-objectivists

If I can give advice to those in pursuit of neo-objective reality, it is this:

We are not interested in what something is, we are interested in where it breaks. What noises it makes when we bend and squeeze it. When it calls its buddies (its corollaries), to what class do they belong? Is it the right class for the question?

Remember, knowledge is not gained from an analysis of ideas when they are at rest, but rather when they are in motion.

This is the same wisdom that tells us different problems are suited to different modes of inquiry, and that we should not attempt to answer a paradox with a paradox.

Apply the tools.

What we discover is reality. It is that final domain beyond which there simply is no knowledge, no meaning, and no existence.

Good luck. Let me know what you find.