Learning to Unlearn

I. Introduction

Why is unlearning racism so hard?

Everyone agrees that racism is bad. On the left, we read and discuss books like White Fragility, How to be Anti-Racist, and Me and White Supremacy, but in our daily lives we’re betrayed: we avoid certain neighborhoods, we send our kids to certain schools, and we frequently assume that all Black people think a certain way (ask a Black conservative.) We date each other, watch movies about ourselves, segregate our social circles, and generally keep a racist system afloat.

Why do we see such a disconnect between our actions and intent?

We become these racial nimbys because we never really learned how to stop being racist in the first place. We attempt to change the image of ourselves in order to feel moral, but we don’t change the foundation of our behavior, the way we think.

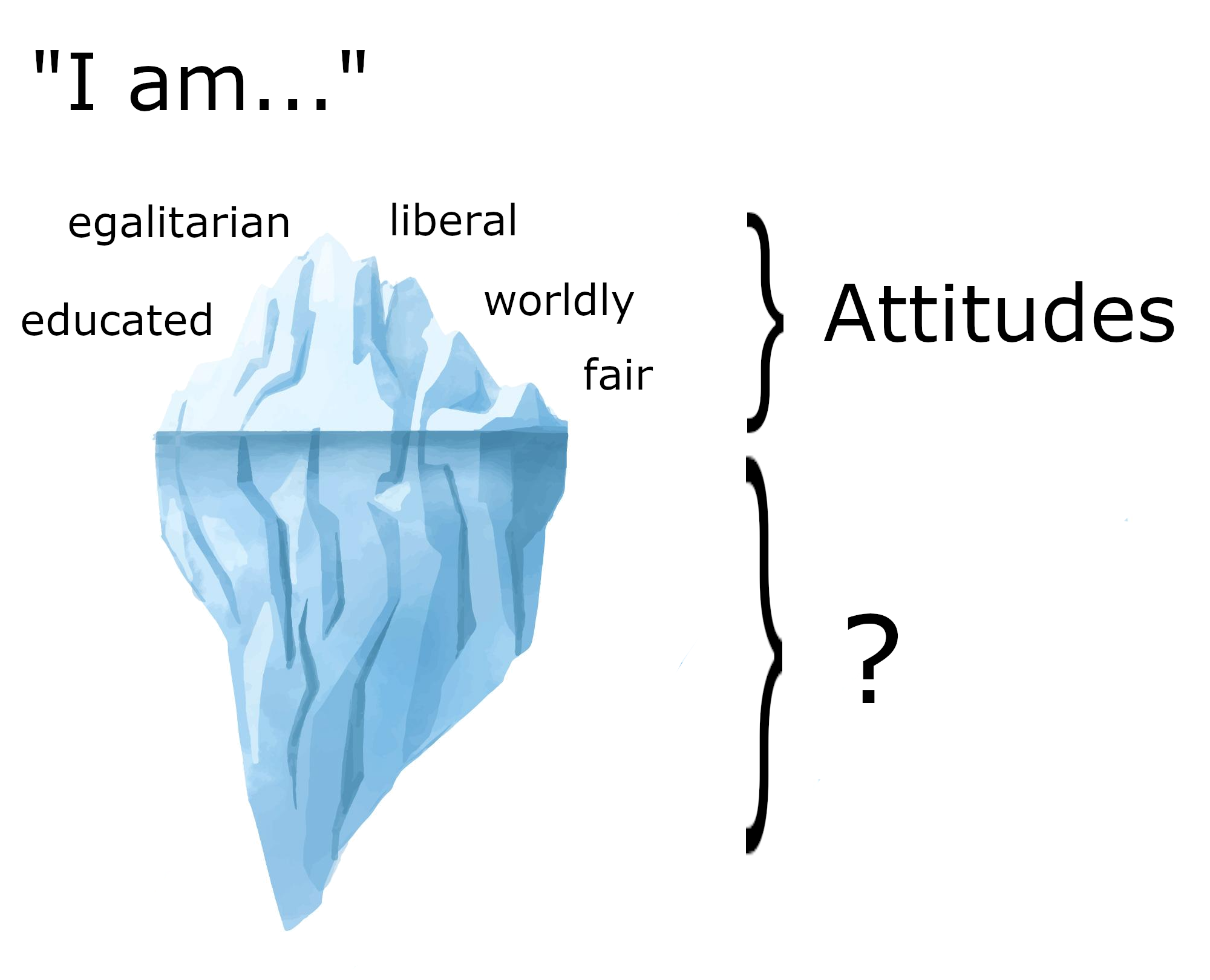

Knowledge of ourselves. What lies beneath?

We’re guided by our impulses, our instincts, who we trust, who we find attractive, and what makes us feel safe or unsafe. It’s what makes us buy houses where we do, what schools we send our kids to, and who we choose to date and do business with. Every racist action we perform is unwittingly driven by a racist instinct, one that hasn’t actually gone away. Not a single book you read can change your instincts.

We examine our actions, ensuring a fair distribution of cheer and goodwill, but policing our behavior treats the symptom, not the cause. Reactionaries call “unlearning racism” performative; that it doesn’t do anything, and so it’s not worth trying. But maybe if we can be smarter about our method, social progress can be made. What we need is an approach to education that goes to the heart of how we act, our unconscious beliefs. To do that, we need to understand the process of learning itself.

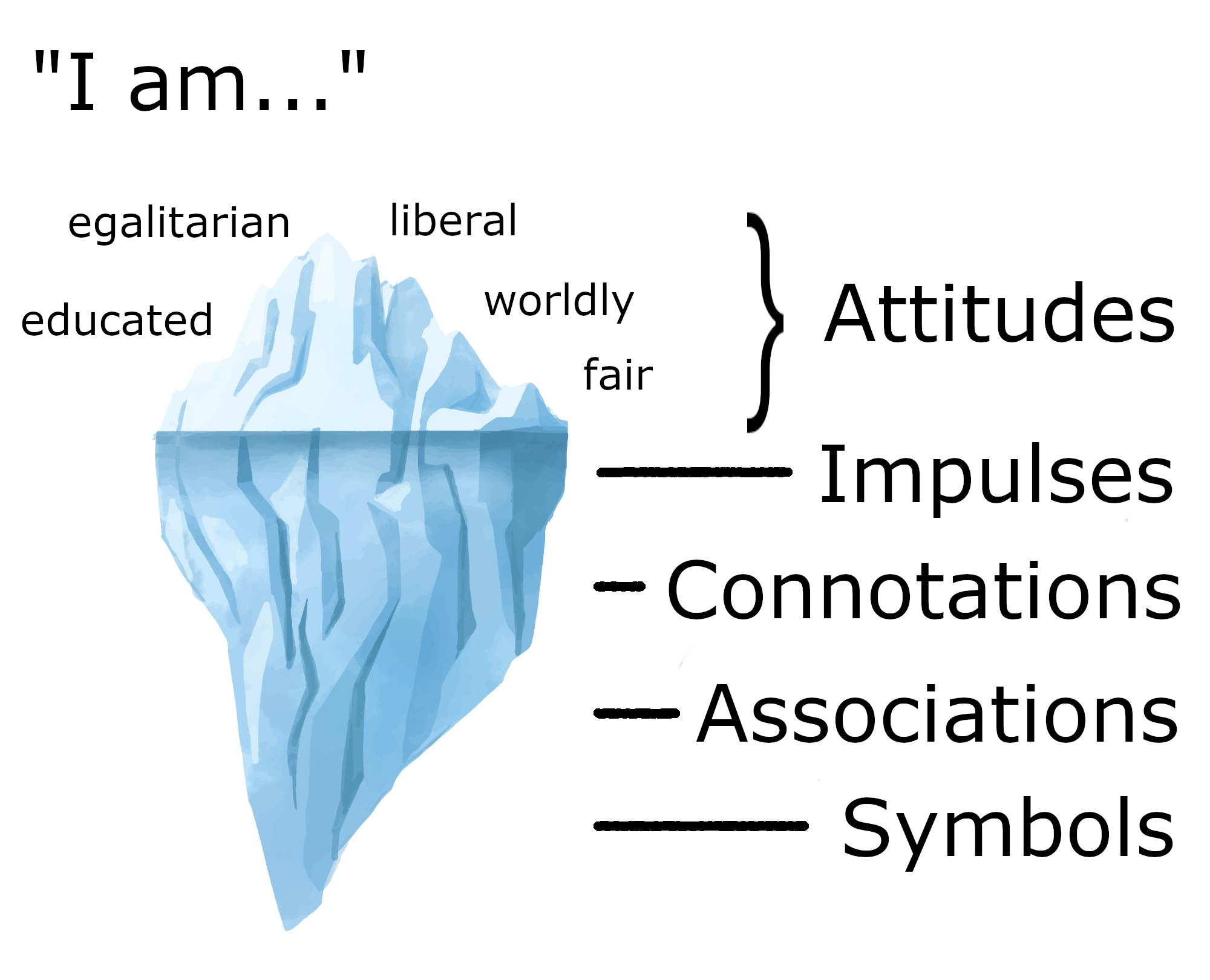

We’re unaware of what we really believe

Capitalism, much like racism, is a psychological problem as much as an economic one1; to replace it, we’ll need a psychological solution. This means moving away from modes of thinking like tribalism, traditionalism, scarcity, and our constant need for incentive.

What I’m proposing is not a new endeavour. In Eros and Civilization, Marcuse identified the “surplus repression” caused by capitalism - by eliminating it, he said, we’d have more social tendencies, like favoring cooperation over competition. John C. Lilly attempted “metaprogramming the human biocomputer”, which meant taking LSD while playing with dolphins, but I’m assuming the reader has neither. An entire industry exists today called “diversity and inclusion training”, which attempts a certain education, though largely with the corporate office in mind.

Most approaches fail because they ignore the fact that people are unaware of what they most deeply believe. Even when we change our minds, we keep the same way of thinking: everything remains a political issue, or a religious issue, or psychological, or economic… We find a framework that works for us, then use and abuse it over and over again until we have an epiphany, then favor this new perspective over and over, ad nauseam.

I’ve cycled through mantras, emulated actors, friends, and authors, dug up niche ideologies, constantly seeking one grand unified theory that explains everything - even when I try not to! Over a beer, I’m an existentialist and an agnostic and I’ll say things like, ‘we’ll never know what’s really true’. But every day I classify and sort and quantify as if I believe we will. Is my agnostic description just a creative license? Deep down, what’s clearly driving my behavior is a belief in objective reality - denying it will do me no favors.

“Wait-- it’s objective! Morality’s objective!!”2

In “Back the Blue”3, I argue that the common trait of Proud Boys, MAGA, Patriot Prayer, and other right-wing protestors isn’t really ideology, it’s personality. As enlightened as we on the left like to feel, we’re subject to the same conditions. The concept we have of ourselves as rational, transcendent beings is false: we all hold positions that we’re unaware of due to our upbringing, our language, and - if you’re a Marxist - the structure of our material conditions. All the theory you read will not fundamentally change the way you view the world because changing opinions requires changing values.

Goal of this essay

I’m interested in learning how we learn in order to reprogram ourselves for sociability, and away from mindsets like commodification and cruelty. Read this as an essay on being open-minded, on how we perceive the world, and the impact that our learning environment has on how we form attitudes and beliefs. In “learning how to unlearn”, we must withhold moral judgment: feeling guilty about the way we’re wired is counterproductive - in order to change our minds, we must first understand them.

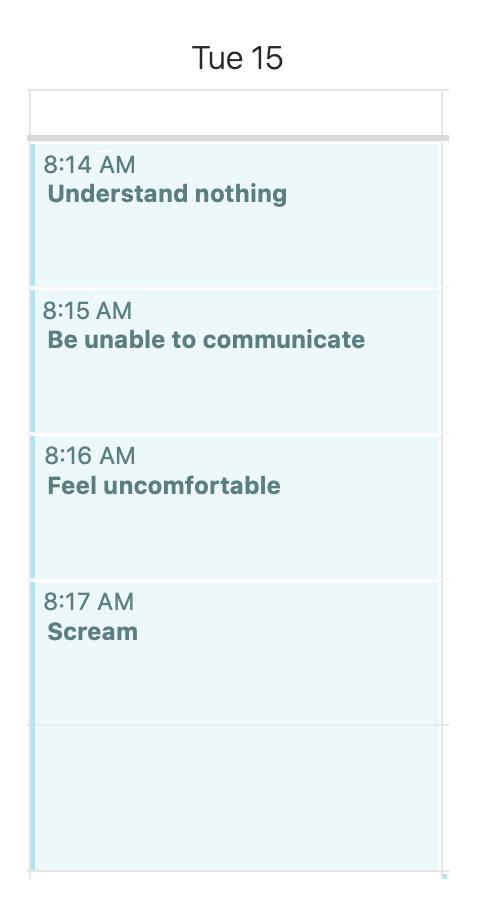

In this essay, you’ll travel back in time to your infancy, exploring your earliest memories. If you don’t have a time machine or an infant nearby, my son has graciously offered to assist.

Has no idea what’s going on

II. Equilibriium

“The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.”

-- William James

In the late 1800s, philosopher and psychologist William James put forth what’s known as the James-Lange theory of emotion4. James argued that physiological changes in our body are the cause of emotion. For instance, we don’t feel fear and then release adrenaline - we release adrenaline (in response to something) and then feel fear. While this theory is not strictly orthodox, proving a bit too simplistic, the general idea has been hard to disprove.

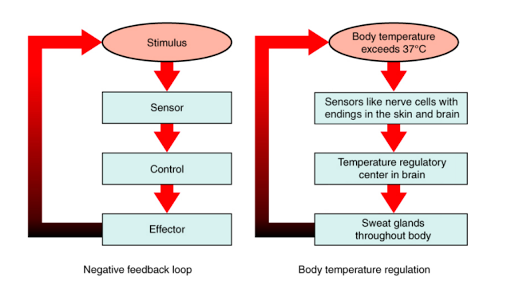

Adrenaline stimulates the body, but we also have mechanisms (and incentives) for bringing expensive processes back under control, returning to an equilibrium known as homeostasis.

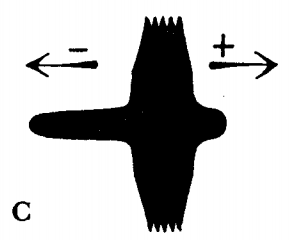

A negative feedback loop is a circuit which feeds its output back to its input.

Your body uses many of these negative feedback loops. When blood sugar gets too high, insulin is released to sequester the sugar. When blood pressure spikes, a hormone is released to expand vessels and increase your blood flow (this is what happens when your dad takes Viagra.)

You’ll find negative feedback loops at levels from the cell, to the organ, to the body. Our brains have negative feedback loops, like our circadian rhythm which creates a steady firing when it’s time to sleep.6 This is why if you’re driving at night, playing steady music on your car stereo can make you feel even more tired.

Consuming 20% of our body’s total energy, it is vitally important that our brains use negative feedback loops to maintain homeostasis.

The nirvana principle

Before homeostasis was a word, Sigmund Freud wrote that our minds unconsciously aim for equilibrium.7 His nirvana principle, responsible for our death drive, posited that all living beings strive to avoid tension and seek equilibrium in the form of death.

Nirvana principle (Cobain variant)

Okay, dark, but let’s focus on just the equilibrium part: our minds, like our bodies, seek to return to equilibrium after stimulation, to homeostasis.

Imagine there’s a large-scale negative feedback loop operating across the brain, cooling things down when there’s too much activity. Through the James-Lange theory, we might expect this process to carry with it an emotional effect, or ‘feeling’ – nigh imperceptible, a subconscious and pervasive mental desire to return to equilibrium. In other words, a biological underpinning of Freud’s nirvana principle.

Stepping back a bit, perhaps we subconsciously adopt attitudes and beliefs that promote this equilibrium, preventing us from having to think too hard all the time and waste our mental energy.

Pattern recognition

"When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail."

-- Abraham Maslow8

Within the realm of sense perception, this ‘cooling process’ works by channeling raw sensory input (stimulation) down into recognizable patterns, bringing us back to a baseline activity level. Furthermore, in the James-Lange sense, I believe we feel the effects of this physiological response emotionally vis-a-vis attaching semantic value to the patterns themselves.

These patterns exist as dedicated neural circuits which channel raw sensory input. The brain likes having large and reliable patterns so it doesn’t have to spend too much time searching and searching for the right one. Recognizing patterns is what allows the brain to identify something, return to equilibrium, and move on.

A simple pattern: my parents fighting.

Patterns that have been useful are reinforced, others are left to wither and decay. Concepts like “race”, “religion”, and “politics” are patterns, albeit very high-level ones. Visual patterns are the most common, but we also form auditory patterns, olfactory patterns, etc.

Some patterns are innate. A cardboard dummy representing a right-oriented bird (hawk) provokes an escape response in newborn thrushes, but a left-oriented bird (goose) does not.9

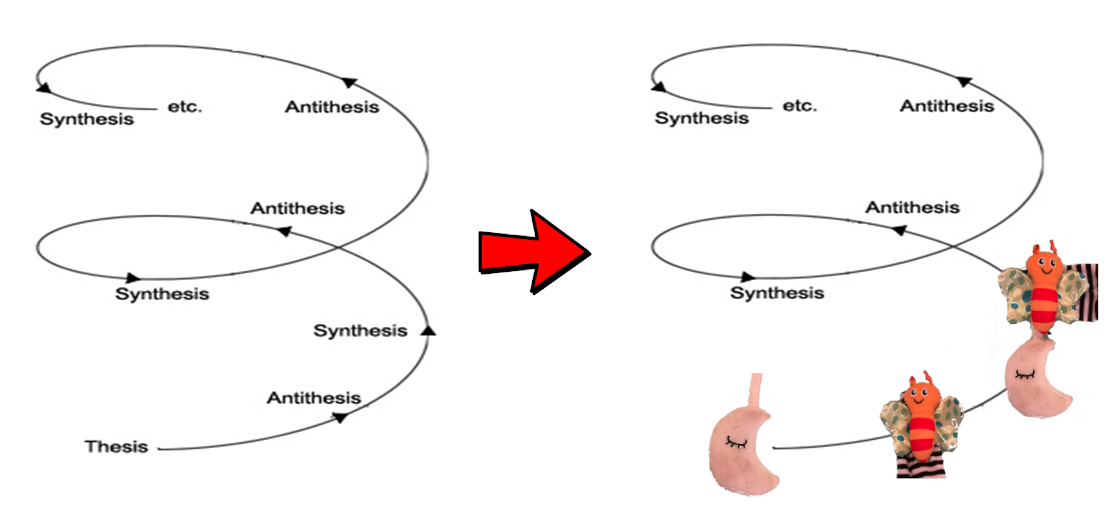

The brain wants optimization. When learning, we try to extend existing patterns rather than create entirely new ones. To Hegel, we synthesize; to Kant, we practice deontology, constantly amending and extending maxims - for example, saying lying is wrong except when it’s to protect Anne Frank or something.

What we experience as equilibrium may seem strange to us - being slightly anxious or excited can actually be our baseline. Bored animals make easy prey, anyway: boredom lowers your baseline activity level, making it harder to quickly respond to dangerous situations. To fight this, we idly stoke our anxiety, replaying past trauma for calibration - to maintain an elevated level of activity.

Whether fighting for our lives or avoiding being bored, we’re constantly engaged in the process of learning.

How does it work?

III. Symbols

“A man likes to believe that he is the master of his soul. But as long as he is unable to control his moods and emotions, or to be conscious of the myriad secret ways in which unconscious factors insinuate themselves into his arrangements and decisions, he is certainly not his own master.”

-- Carl Jung, Man and his Symbols

You probably saw a circle at first. Why is that?

According to Hebbian theory, over time we’ve built close physical connections between our neurons. They’ve become so closely enmeshed that the firing in one triggers a firing in the other.10 In the case of the semi-circle, our brains contain a Hebbian circuit dedicated to perceiving circles. Stimulate enough of the neurons involved, and the rest will follow.

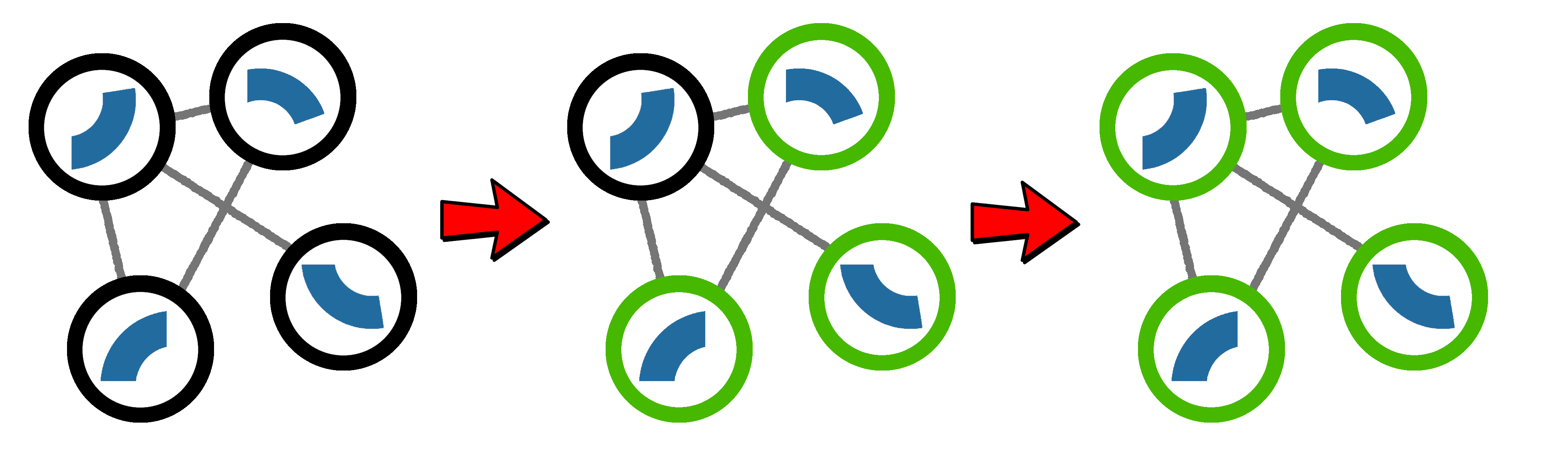

a) our Hebbian circuit for a “circle”; b) enough nodes fire and so, c) all nodes fire

Every node in the circuit above is itself a smaller Hebbian circuit, with nodes that more closely map to direct sensory input.

Our brain is constantly trying to find the right circuits for each piece of sensory input – more specifically, we want to find the best ones quickly so that our brain can conserve energy. Once the stimulus has been identified and understood, the brain can forget about it and move onto other, new stimuli.

Reinforcement learning

The first circuits the brain turns to are the ones that have been successful in the past.

If a stimulus is ‘understood’, all circuits that participated and were found to be useful are strengthened, or reinforced. Circuits that participated but were not found to be useful are not reinforced. In fact, they’re slightly penalized for having fired (expended resources) without being reimbursed, so these circuits slightly atrophy.

In the semi-circle example above, the ‘circle’ circuit is not reinforced, our ability to detect a circle slightly atrophies, and we continue the search until we can find a circuit to explain it. Artificially, we can keep this search alive by idly staring at objects that no longer should be interesting. We can disassociate them, invent fantasies, imagine them in new places, and picture ourselves interacting with them in strange ways.

If a stimulus cannot be explained by any circuits, then a new one must be created. This is an expensive process but is the first step of learning, which I will talk about more shortly.

Higher-order circuits

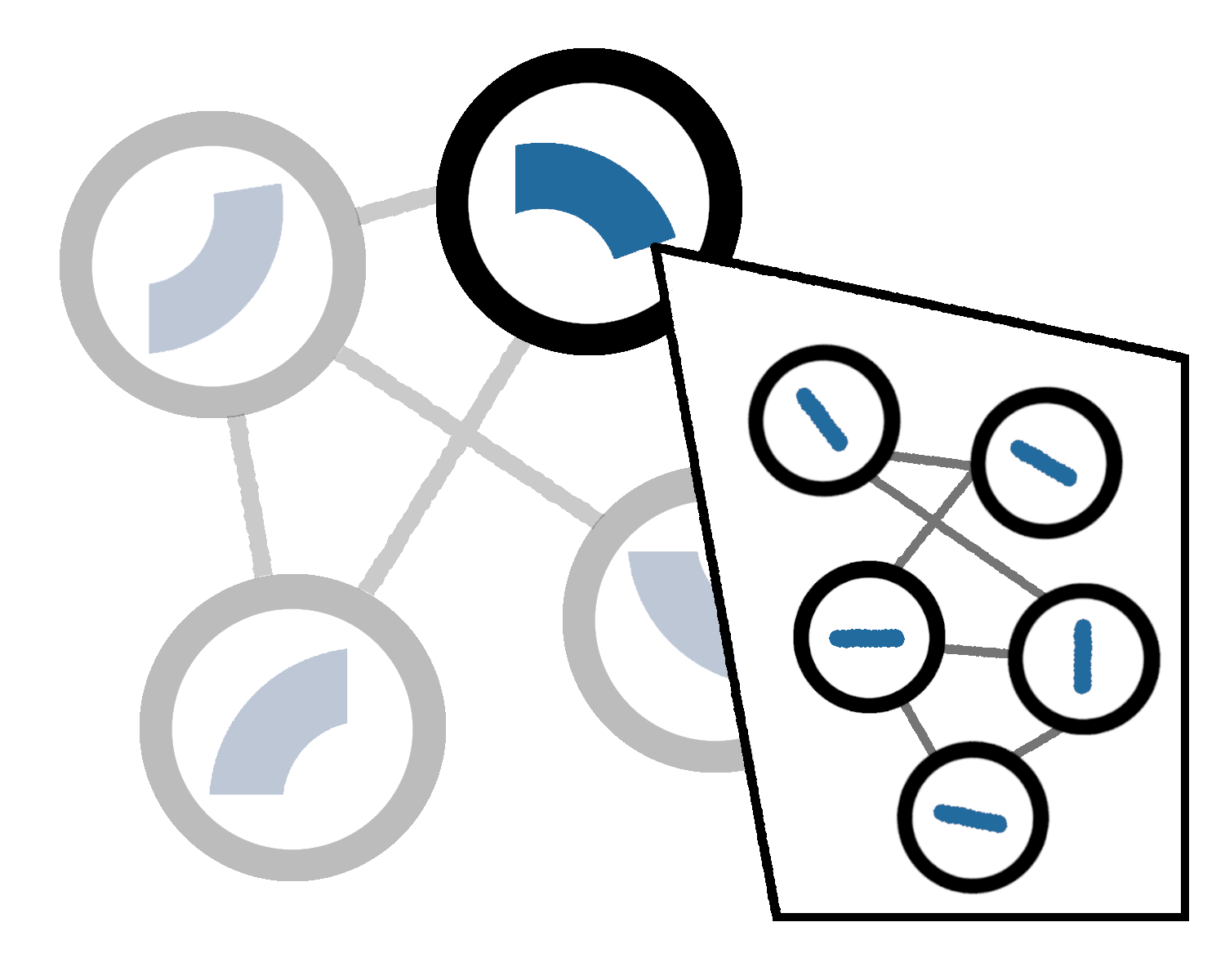

If we understand that a symbol like a circle exists as a Hebbian circuit (or a circuit-of-circuits), could we extrapolate to say that smaller symbols act as nodes for larger, more complex symbols?

Let’s imagine a table, for example.

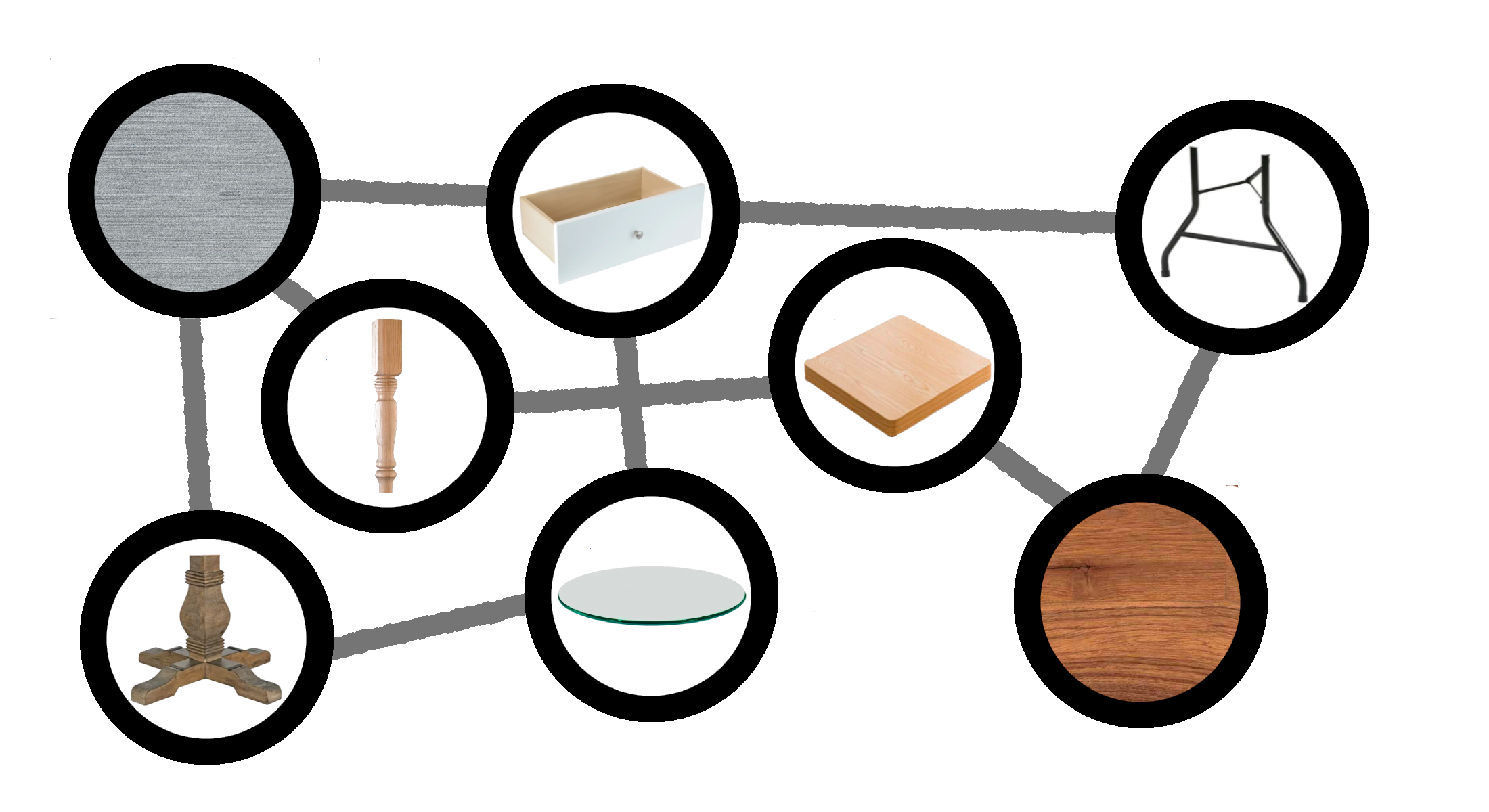

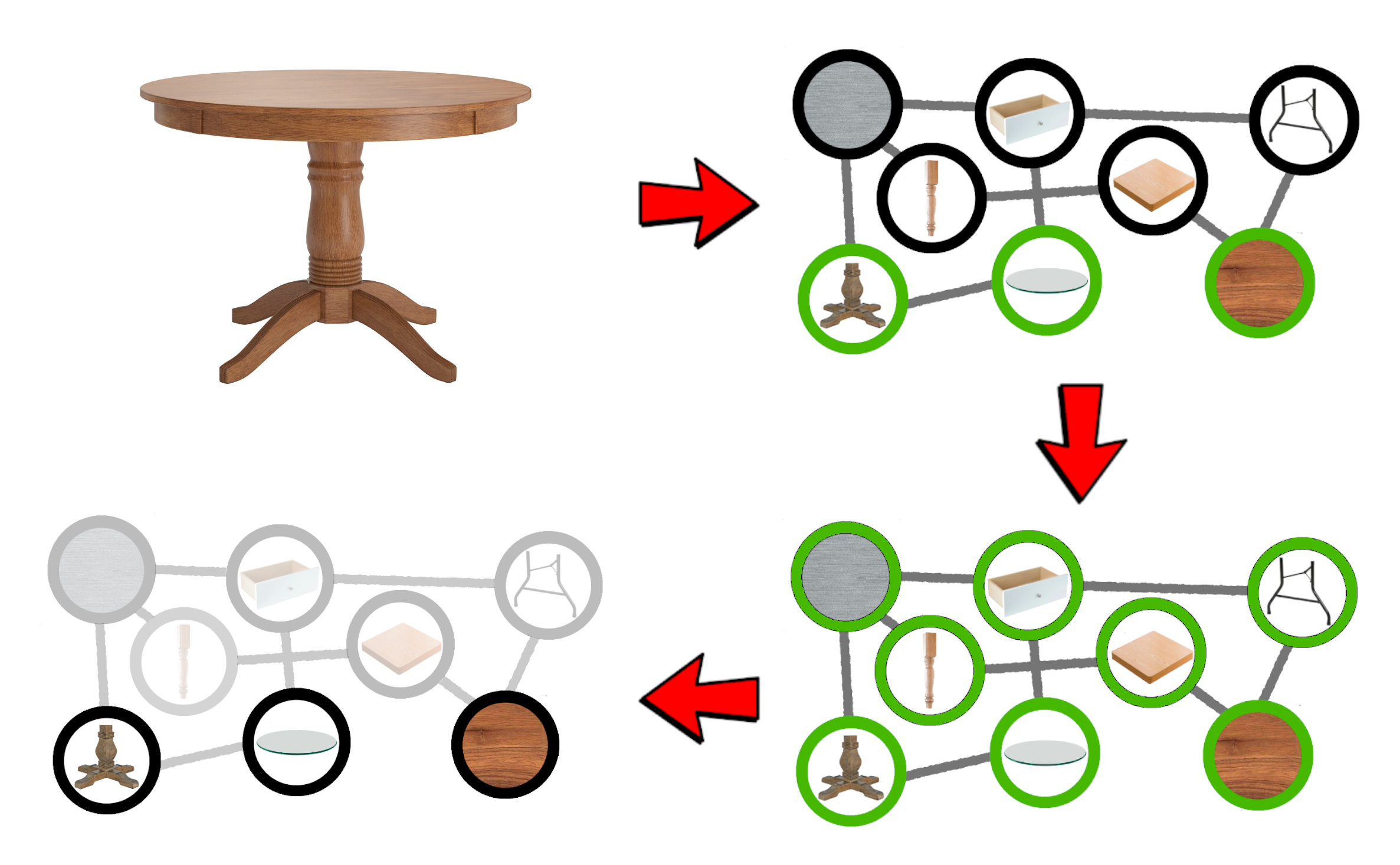

A Hebbian circuit for a “table”, each node is itself a circuit of a simpler symbol

(clockwise) a) When we experience a table in real life, b) certain symbols in the circuit match and fire. c) If enough fire, they all fire and we perceive the stimulus as “a table”. d) Useful circuits are reinforced; the rest slightly atrophy.

One might call a higher-order circuit like the one above the “Platonic form” of a table. It’s what our mind’s eye produces when we’re asked to conjure up a table.

If we kept coming across round tables, eventually we’d imagine all tables as round - rarely ever square. Because round and square tables are somewhat evenly distributed in real life, the two nodes are continually reinforced and atrophy, forming an equilibrium. We continually extend the circuit, adding new nodes, as we come across new tables.

*slaps roof* This bad boy can fit so many tables in it.

A highly evolved symbol, like “father” or “mother”, is a circuit which has proved itself useful many, many times through the formative years of our lives. As humans, we have a preference for useful symbols, we construct complex symbols from simpler ones, and we perceive reality itself as a collection of symbols.

Associative learning

Learning, in part, is the acquisition of new symbols.

Imagine you have an infant and you’d like to give him a new toy. When you introduce it, what do you do? You coo and laugh and sing and smile. This helps him form a positive attachment.

My son’s first toy: a felted crescent moon.

When I first showed my son this moon toy, he began to search it for clues - features he already knew. He cycled through symbols in his mind with lightning speed, gauging if this toy was friend or foe. For some people this process never fades in the background, and can feel quite disorganized or debilitating. In an academic setting, we can spend as much time as we want asking about the true nature of a thing but in a moment of danger, a frying pan is the same as a baseball bat.

Eventually, no symbol fully matched and Owen was forced to learn a new one, moon. My cooing, which created a positive learning environment, is itself a symbol - one he learned previously through association with something else. There’s nothing inherently good about cooing - instead, it was present when he was bounced, rocked, swaddled, and fed. Ultimately, every symbol can be traced back to our primal needs for food, warmth, and sleep.

*breathing intensifies*

This is not a paper about evolutionary psychology, though. While some knowledge is innate (like ‘food is good’), acquired knowledge still provides a cogent foundation for our behavior.

L’enfant terrifié

For the first few months of an infant’s life, they follow a simple, daily schedule.

It is absolutely terrifying.

A change of clothes can turn into a petrified last stand - his final battle - with the parents unable to calmly intervene and defuse. As he grows older and learns more, he’ll experience fewer and fewer moments of raw psychic pain. Over time, terror yields to mere frustration - he knows he won’t die, but he still can’t use his mind to make the tall people do what he wants. He learns to manage this frustration by self-soothing - e.g. sucking his thumb - taking a positive association he’s formed (sucking is good, since that is how he eats) and using it to calm himself down. This emotional reliance on symbols forms the basis of our abstraction: he’s wet, therefore he sucks his thumb.

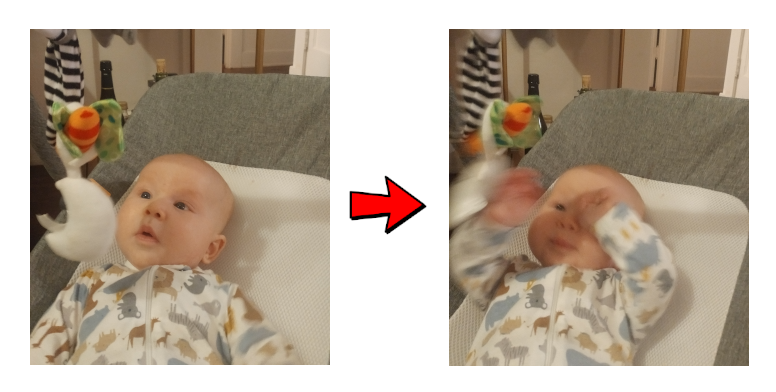

As an experiment, I strapped a new toy, a butterfly, to my son’s moon. Owen was very apprehensive about this chimera, moon-butterfly, staring intently at the new feature. He had some prior knowledge (moon), but not enough to explain the whole thing. Behind his tiny little eyes, his brain worked in overdrive, scanning the new object for any signs of what it could be - the color, shape, texture… - his brain struggling to get this frenzied process under control.

a) Hegelian dialectic b) learning new symbols from old ones

Eventually, he learned two new symbols, butterfly and moon-butterfly, and formed an association between moon and butterfly. In the future, seeing moon could make him think butterfly. These fledgling symbols are weak and, if they prove their mettle, will grow larger over time. Symbols forged during trauma - a failed timely understanding ending in pain - are much, much stronger.

Once we understand something, then we can ignore it and return to equilibrium, ready to perceive the next thing - Freud’s nirvana principle at work. This is why you’re usually unaware of your own breath, or how your tongue is filling up your mouth, or how you’re reading this in your own voice.

Positive and negative connotations

When an infant learns a symbol under duress, it will be given a negative connotation. If he learns it in a positive environment, or with expectation of reward, it will earn a positive connotation. Connotations can range from extremely negative to neutral to extremely positive.

| Common | Uncommon | Rare |

| No connotation | Moderate connotation | Strong connotation |

There’s an inverse relationship between the frequency of a symbol and its connotation. If you see a symbol everywhere, it will come to mean nothing.

When we get hurt, all participating and useful symbols are negatively graded (positive ones become less positive, negative ones become more negative.) Conversely, if we experience a reward then participating, useful symbols are positively graded.

The two attributes of a symbol, besides the nodes which make up its circuit, are its strength (reinforcement vs. atrophy) and its connotation (positive or negative).

Has picturing a negative symbol ever made you recall other negative symbols, or a positive symbol made you recall other positives? For instance, if you picture the flag of the United States do you see jets dropping bombs in Iraq? If you picture the flag, do you see a bald eagle soaring over a stream somewhere in Idaho?

When recalling an associated symbol, or ‘associating’, such as recalling butterfly from moon, we prefer symbols that are themselves strong. Strength being equal, we prefer ones that share the same connotation (positive or negative).

Symbols with a positive connotation make you more likely to recall positive associations (associated symbols which are themselves positive).

Symbols with a negative connotation make you more likely to recall negative associations.

Learning environments

When we don’t have enough information, we look at the connotation of associated symbols, using them as context clues.

Imagine you spot a diplomat’s car driving down the street - sleek, black, tinted windows, and a flag. You know nothing about who’s inside, but you start to form an impression of the person based on the symbols you know.

The overall context is the net result of all context clues (the positive and negative connotations of associated symbols). If the context is negative, we’re in a negative learning environment. If the context is positive, we’re a positive learning environment.

If you’re in a negative learning environment, you’re more likely to recall negative associations, making you more likely to form a negative connotation of whoever ends up being in the car. If you’re in a positive learning environment, you’re more likely to give this person the ‘benefit of the doubt’.

IV. Aesthetic

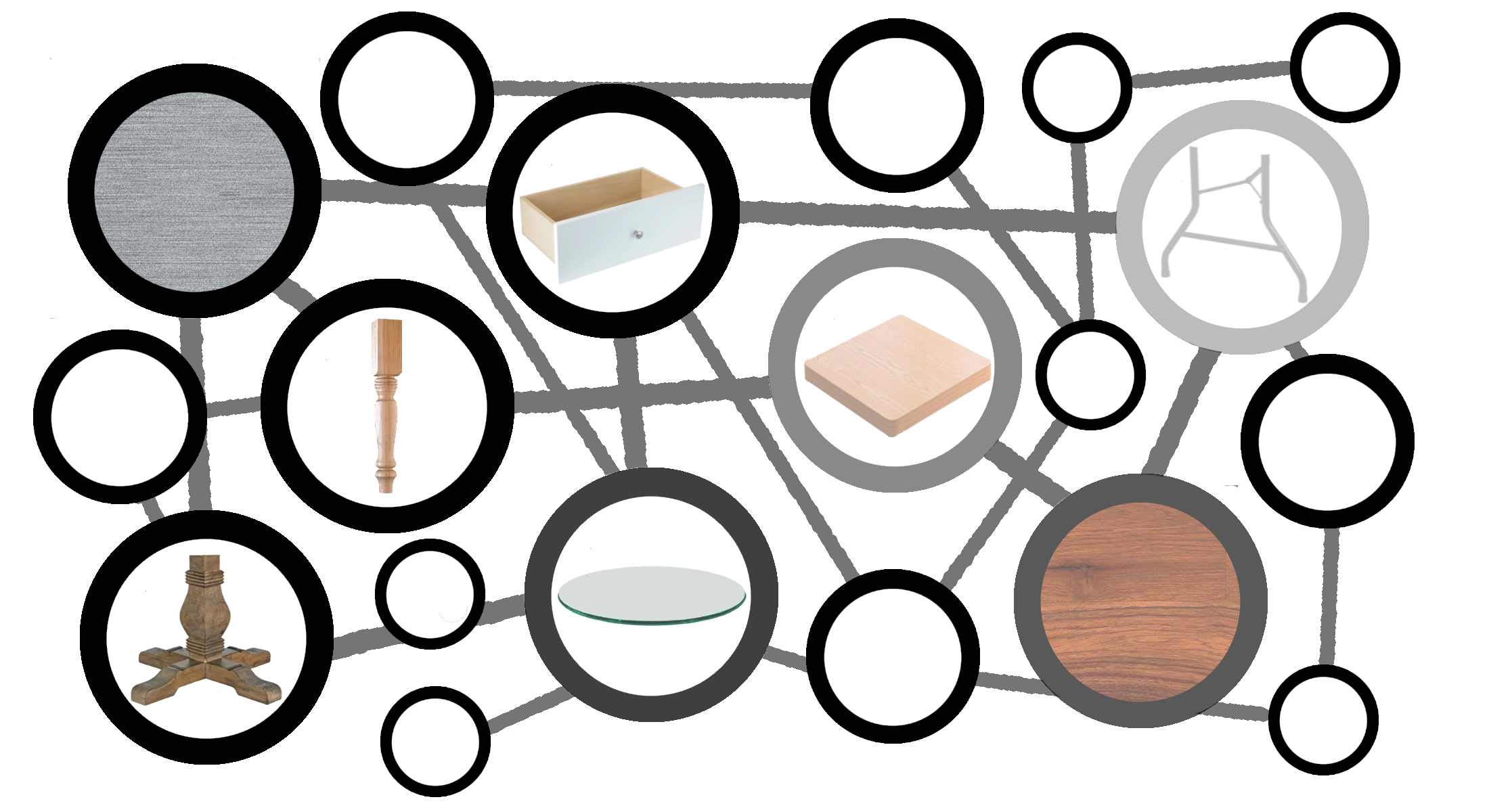

Our constellation of symbols, with their positive and negative connotations and associations, forms a landscape known as our aesthetic, or taste.

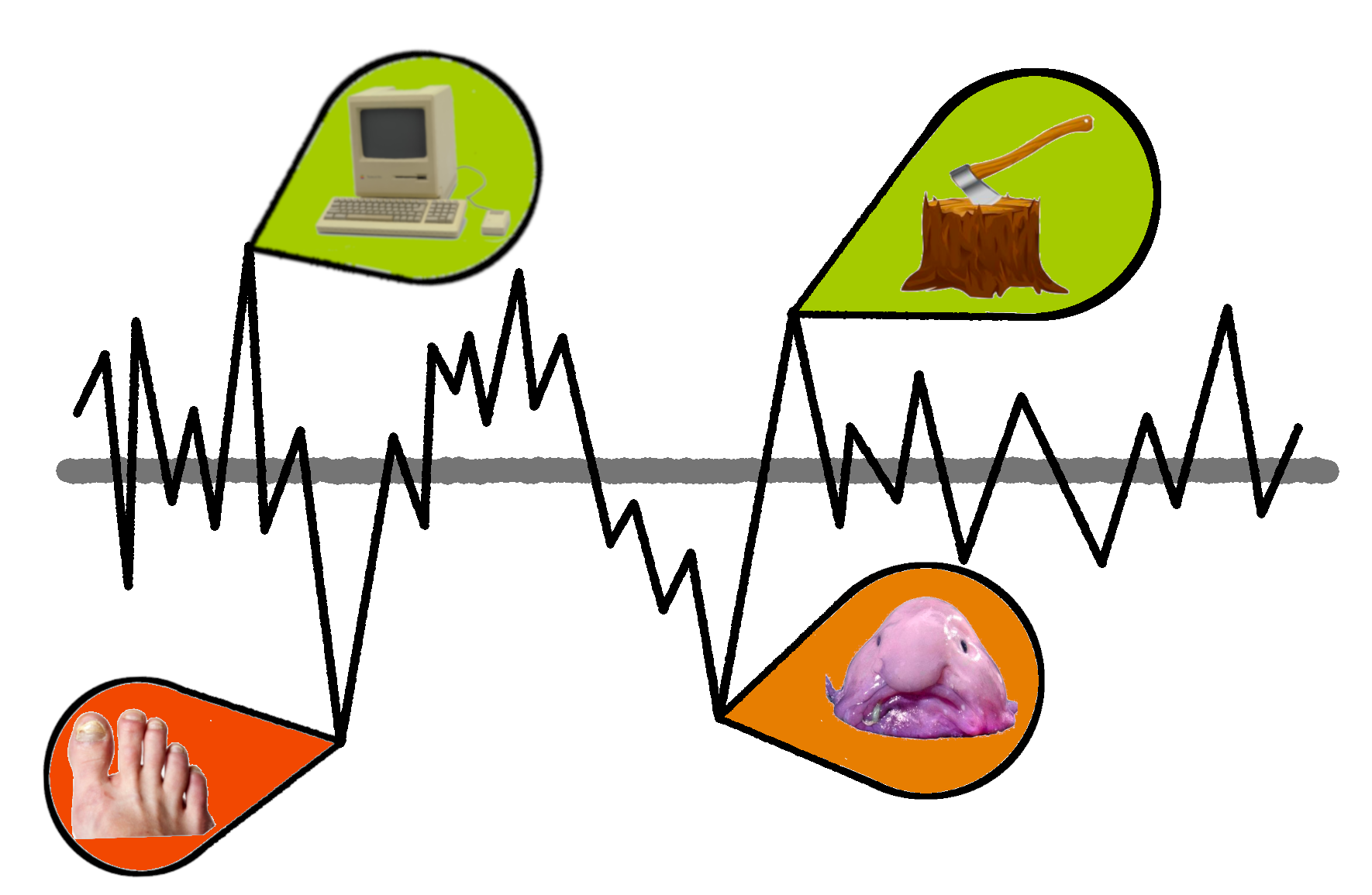

A sample aesthetic

Our aesthetic comes out in our lifestyle choices: we surround ourselves with symbols we know and are familiar with, so we don’t overload our brains (the ideal decor is meant to go unnoticed.)

Aesthetic, however, is more than just what you post on Instagram - it’s how we detect threats as well. Symbols like large, sharp, hot, and blood provide important context clues that alert us to something bad about to happen. Unfortunately, these markers also include things like skin color and the way someone’s dressed. Our aesthetic has real social consequences.

We perceive each other as symbols

To my son, I’m not me - I’m “dad.” As symbols, we carry positive and negative connotations to each other, borne out of past pain or pleasure. I’m there when my son eats, but I’m also there when he’s hungry. His symbolic interpretation of me, the father, is continually being positively and negatively graded, as well as reinforced and atrophied.

If you meet a man who looks like your father, you’re using one of your oldest symbols to apprehend this new character. You’ll look for other attributes of your father, too, because it’s the easiest way to understand them.

This explains the eerie feeling of seeing one’s doppelganger - you immediately feel you understand them, and your brain is surprised at not having to do anything. This feeling of absent labor is what we call the uncanny, or unheimlich. Nostalgia operates along a similar line. You have ancient, atrophied pathways from your childhood gathering dust. Suddenly one node is stimulated, others follow, and your brain is awash in old association, stunned at the activity.

The Trinity of modern capitalism

As symbols, we’re part of each others’ aesthetic landscape. A violation of aesthetic, or disgust, is often what drives one to be a conservative.3,11 The stereotypes and biases we hold are based on connotations and associations that we’ve learned. We often confuse aesthetic with morality, treating the beautiful as good… which is why Ted Bundy has a fan club.

Social cohesion is highest when people share a similar aesthetic, which is why war - with its common negative imagery, or propaganda - promotes domestic unity. To achieve social cohesion without resorting to war, however, we must intentionally broaden and re-examine our own aesthetic. If your aesthetic is too narrow, you’re more likely to find the Other threatening.

Reprogramming our aesthetic

Because we constantly acquire new symbols, form new associations, and adjust our connotations, we can devise a strategy to reprogram our aesthetic, one that should lead us to social impulses and behavior.

At this point, we have a much better sense of how our attitudes are formed.

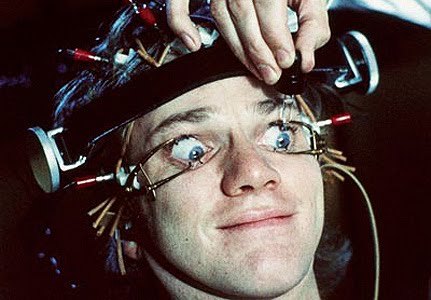

We should be reprogramming our aesthetic with this model in mind, introducing positive symbols and reinforcing them, and letting negative symbols atrophy or be associated with positive ones. As a society, the best use of our money is creating positive learning environments in our public and private schools, but we can apply the same principles to our own lives, exposing ourselves to negative symbols while creating a structured, positive learning environment.

This but unironically12

Leave your guilt at the door

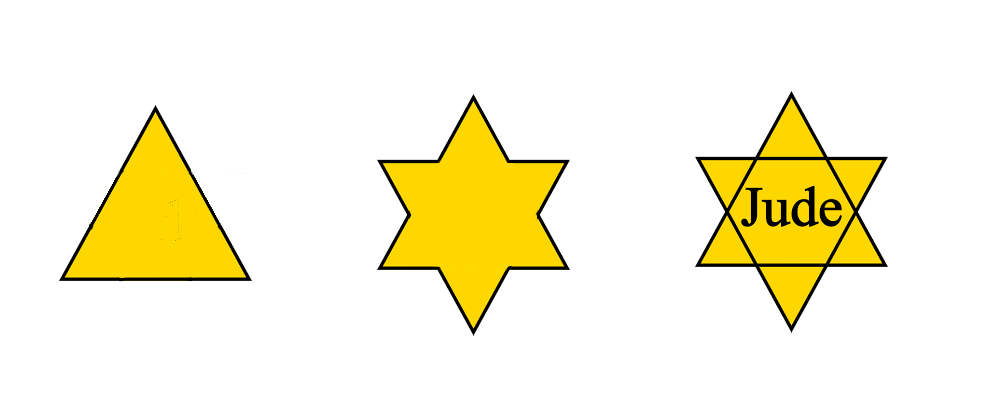

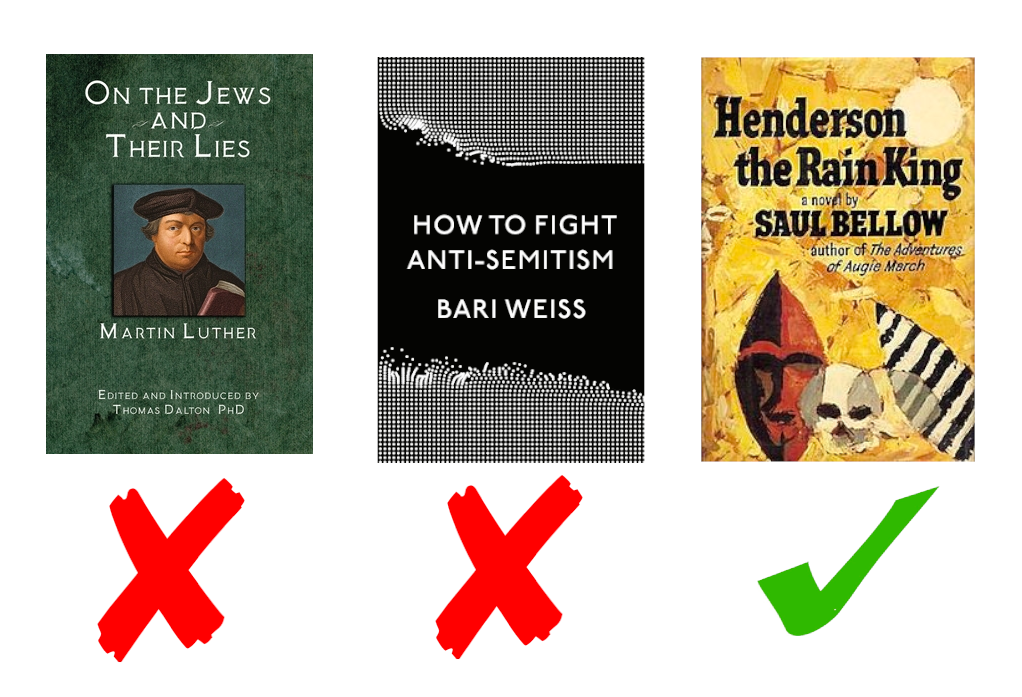

Feeling bad about being White can be useful, especially if it moves you to re-examine your behaviors. Where it becomes a problem, however, is when this guilt and shame is persistent through everything you read or consume. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t read books like How to be Anti-Racist or The Diary of Anne Frank, but that our education should not primarily consist of painful stories set against a backdrop of injustice (unless that’s your thing.)

If you’re exposing yourself to Black skin color within an environment of guilt, you’re creating a negative learning environment which makes you less likely to come away with a positive connotation: instead of thinking about crime, now you think about slavery. We can’t remove negative impulses by continuously associating injustice with self-loathing. We won’t wake up, we’ll just be more condescending.

If you want to improve your view of Jews, consume enjoyable media

White people working towards Black liberation should be engaged in unabashed celebration of Black people and culture. Consume so much Black media that the symbol of Black skin becomes like the yellow triangle: ubiquitous, and therefore meaningless. Watch Black comedy, listen to Black podcasts, watch Black movies besides Hidden Figures and Twelve Years a Slave. Watch The Boondocks, Insecure, Dear White People, and Sorry to Bother You. Spend less time posting about White supremacy to your White Instagram followers, and get together to watch a Black movie instead.

By intentionally cultivating positive connotations with symbols like Black skin, Black dress, Black hair, Black food, eventually the idea of Blackness as anything negative will fade. Black neighborhoods will seem less scary, Black candidates will shine brighter, and we’ll stop participating in identity politics to the point where we can take action along class lines, together.

Citations

- The Red House on Mississippi

- r/philosophymemes, Reddit

- Back the Blue

- James-Lange Theory, Wikipedia

- Biology LibreTexts, UC Davis

- A molecular mechanism for circadian clock negative feedback. Duong HA, Robles MS, Knutti D, Weitz CJ. Science.

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Sigmund Freud

- Law of the Instrument, Wikipedia

- Social Releasers and the Experimental Method Required for Their Study. Niko Tinbergen. The Wilson Bulletin.

- Hebbian Theory, Wikipedia

- The Strange Politics of Disgust, Dave Pizzaro. TED

- A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.

Summary

We’re not good at unlearning racism because we focus superficially on behavior. Capitalism is a psychological problem which requires a psychological solution. Freud’s nirvana principle is really a negative feedback loop in our brain. During perception, we unconsciously strive for equilibrium by detecting patterns or symbols and attaching semantic value. Symbols are Hebbian circuits; complex symbols are built from simpler ones. These symbols, with their associations and connotations, form our aesthetic. If we want to change the root of our behavior, we should look to change our aesthetic, which can be done by consuming enjoyable media without guilt or self-loathing.