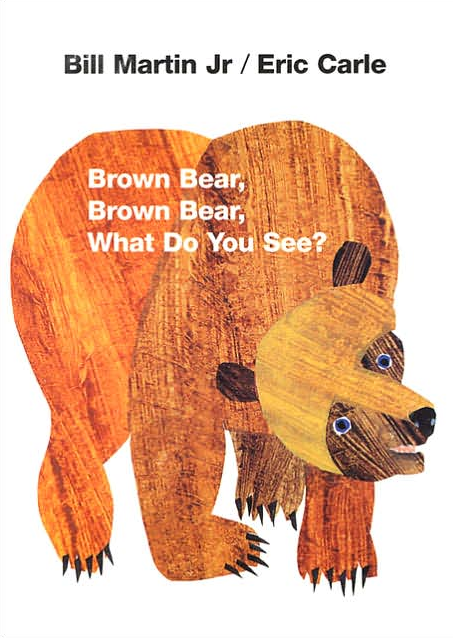

Brown Bear, Brown Bear: A critical analysis

In 1967, educator and publishing executive William I. Martin Jr. (known to his friends as “Bill”) teamed up with then-unknown designer and illustrator Eric Carle to publish what has come to be known as the short story, Brown Bear, Brown Bear.

Selling over 7 million copies and producing several successful spin-offs, the message contained within Brown Bear, Brown Bear was transmitted without hesitation to an entire generation of American schoolchildren. What exactly was this message? Was it a fanciful tale blending the worlds of animal and man? Or was it a ham-fisted bourgeoisie creationist myth dressed up in children’s fantasy, distributed to the next generation of proletariat in order to spread false consciousness?

To understand the meaning behind Brown Bear, Brown Bear, we must first examine the authors themselves. Bill Martin, son of a traditional Christian couple from Kansas, experienced a childhood marred by dyslexia, sibling rivalry, and the ever-present “homesteader spirit” that was ubiquitous in Kansas during the Great Depression. While of modest means, this turbulent childhood prompted Martin to join the American war machine: it was while serving in the Air Force that he produced his first major work, The Little Squeegy Bug. A Kafkaesque nightmare of industrial depersonalization, the story goes as follows:

Once upon a time there was a little squeegy bug. No one knew where he came from. He wasn’t an ant. He wasn’t a cricket. And he certainly wasn’t a flea. What was he?

Predating both Levi-Strauss’ work in structuralism and Sartre’s most cutting work in existentialism, this piece harkens to a future in which man’s own definition is ripped away from him by the post-Fordist capital machine. Impressed with Martin’s zeal, Eleanor Roosevelt (the second-most powerful liberal of the day) promoted his message through her propaganda arm, a newspaper column cheekily called “My Day”, cementing Martin’s place within post-war America’s purposeful and pernicious expansion of the big Other.

Eric Carle, Martin’s illustrator and collaborator, fought on the German side of the Second World War. Captured by the Red Army, he returned home weighing only 85 pounds; according to his wife, he routinely suffered from post-traumatic stress. After fleeing the communists, he found refuge in America and quickly ensconced himself in its holiest institutions, finding work at both the New York Times and later the U.S. military during its imperial operations in Korea.

Carle and Martin joined forces in 1967, the same year that French theorist Jacques Derrida published his lecture Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences, kicking off Europe’s period of post-structuralism. It was the same year that the Situationist Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle, a scathing rebuke of capitalism. With the student riots of May ‘68 looming on the horizon, it became imperative that Carle and Martin work to prevent America from following France’s lead into radical class consciousness.

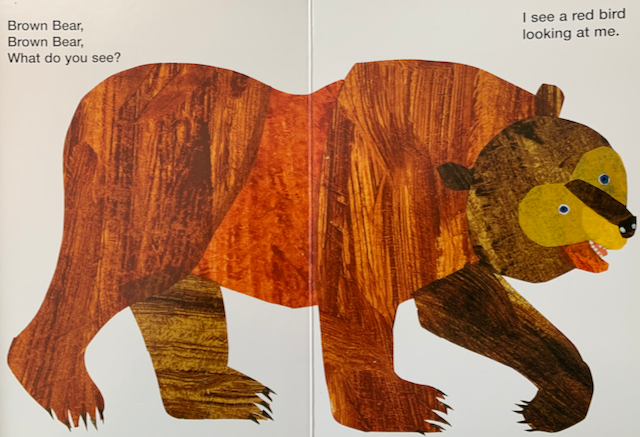

The story opens with the eponymous brown bear:

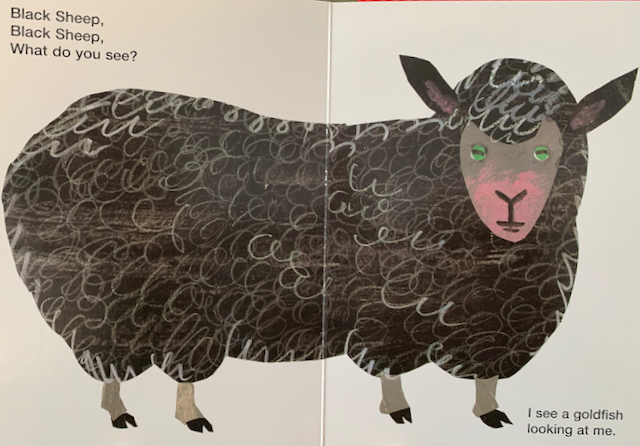

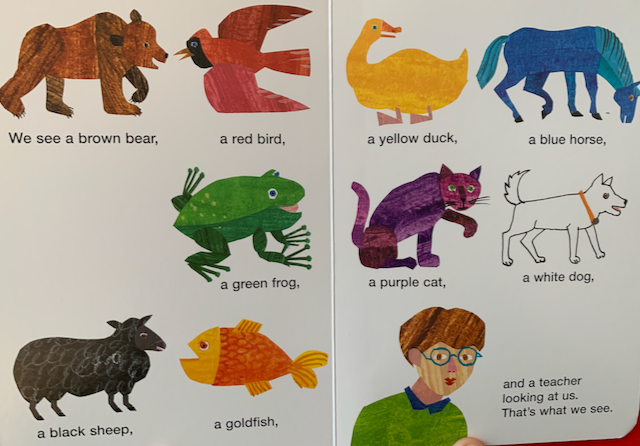

Obviously, the bear represents death. What interests us, however, is why is the bear brown? Martin associates the color brown with the bear but also establishes that the bear must be brown - what of black bears or polar bears or panda bears? (These will be addressed in a subsequent essay responding to Martin’s oeuvre more generally.) Suffice it to say, by positing that the bear is brown we are reminded of shit - shit, in French, being merde - a close homophone to mère, or mother - a dig at the French revivalism of psychoanalysis under Lacan.

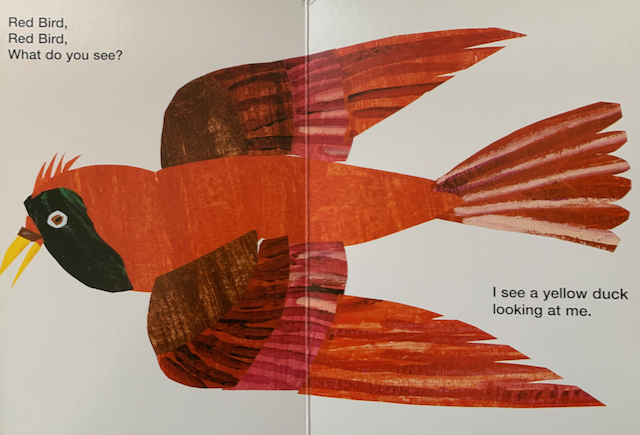

The red bird of the next passage, on the other hand, represents life. A bird is free to fly around, lofting high above the constant machination of capitalism. To Martin, the red bird represents the revolutionary spirit of Debord’s Situationist movement (red, of course, being a clumsy allusion to communism.) He continues:

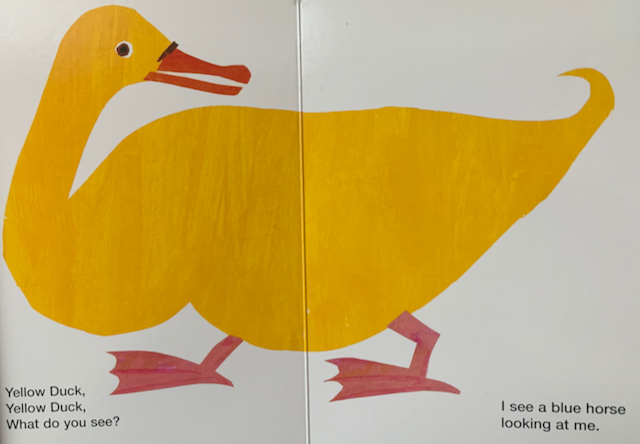

This is where Martin’s military background begins to shine. By contrasting the abstract “bird” with a particular type of bird (a “duck”), Martin throws in our face the indefinable character of life itself. We are used to thinking about life in the abstract (“bird”), but when presented with every-day reality we are forced to reify this symbol into a concrete one (“duck”), thus matching the expectations of the big Other and losing sight of life’s essence.

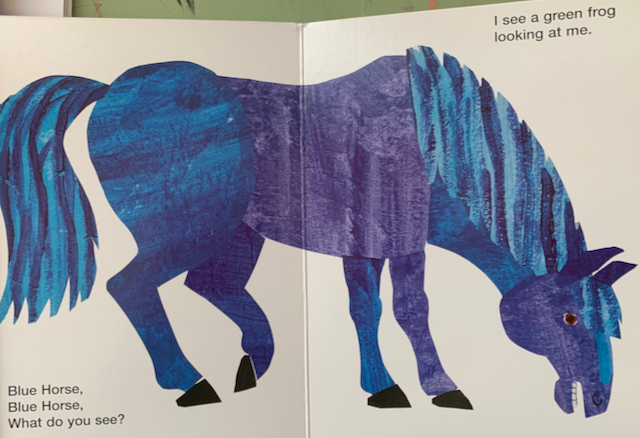

At this point, Martin and Carle present us with incontrovertible absurdism - sure, we can believe in a yellow duck (we’ve all seen one), but a blue horse?! Here, Martin is expecting us to recoil in horror - it is only natural. Invoking the Bard’s mastery of the biopolitics of language (Shakespeare’s “horse of a different color” from Twelfth Night), Martin summons the linguisto-commercial apparatus to hammer out any last hope of meaning, forcing the reader to confront the banal absurdity of life under capitalism. Where does he redirect the reader’s subsequent anger?

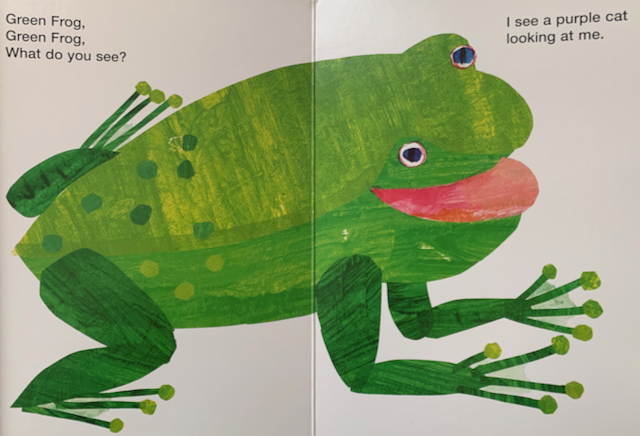

The anti-semitism in this section is a stark reminder of neoliberalism’s ability for obfuscation - its preference to remain invisible - and is, unfortunately, entirely expected: green (money, ‘greenback’, the U.S. dollar), and frogs (from the Egyptian plague in the Jewish myth of Exodus.) In other words, Martin asks, ‘Who has subjected us to the absurd condition in which we are detached from any sensible essence of (or access to) humanity? The Jews.’

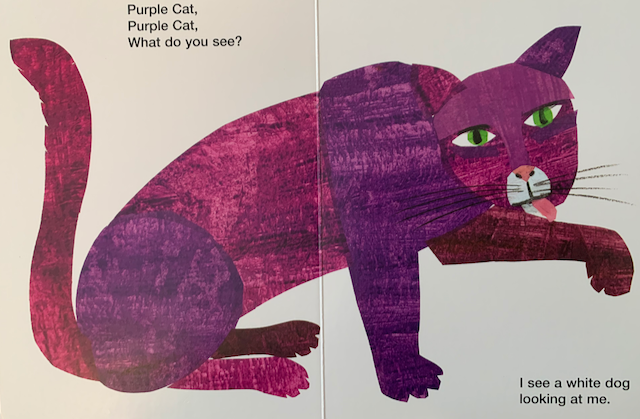

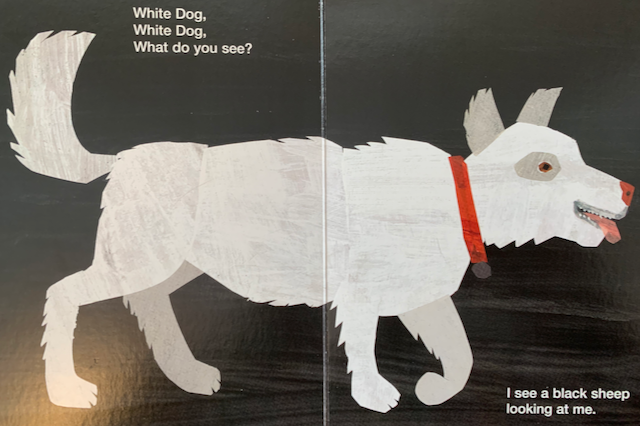

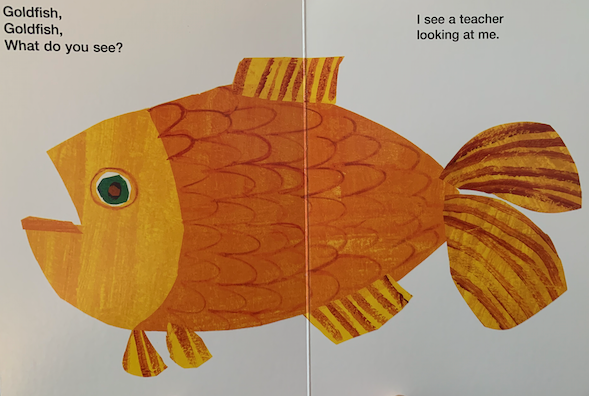

These four lines must be taken together to make any sense of them. The purple cat, of course, is lifted from the feline polemicist of Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland whose message is, “all we can do in the face of absurdity is smile” (perhaps also Martin’s appropriation of Camus’ 1942 essay, The Myth of Sisyphus.) The white dog is our implicit acceptance of the violence of white male patriarchy and, at the risk of spoon-feeding the reader, the black sheep represents anyone who dares question (to their own social circles) Martin’s tautology of alienation, serving as a painful injunction that any resistance is futile. Finally, the goldfish is a somber reflection on attention and memory itself: even if we attempt to resist, we shall soon forget that which we oppose.

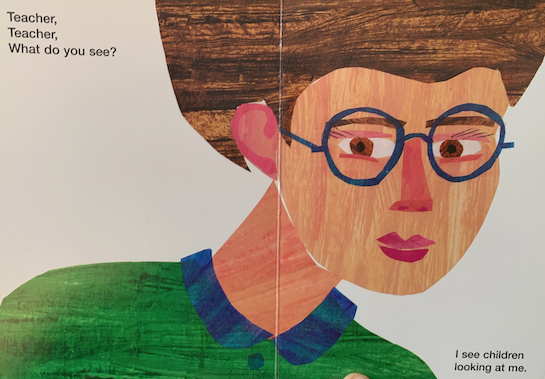

At this point, Martin brings us back to the big Other: the nameless, faceless teacher at the head of all of our classrooms. Already we have forgotten the painful contradiction of capitalism (the hallmark of one being a goldfish), and our attention is brought back under the purview of the vessel of capitalist’s structural reinforcement: early childhood education.

Looking. Staring. Drooling. The schoolchildren, Martin teases, have been reduced to juvenile blank stares, ready to accept at once surrender to the ontological guardian of the symbolic order. With tortured smiles on their faces Martin scorns leftists from past to future.

Indeed, as Martin claims, “that’s what we see.” Today, in an age of climate change, postmodern nostalgia, and crippling irony anyone who dares to resist the insidiousness of late stage capitalism must be willing to ask of him- or herself: What else can we see?