Background

To me, history has always seemed like a scatterplot of disconnected dots. I’d learn about one narrow lane of history at a time, like the American Revolution, and feel frustrated that I couldn’t recall specific enough dates to correlate what was happening in other parts of the world.

For example, while America was fighting Britain in the War of 1812, Napoleon had swept across Europe and dismantled one of Europe’s most powerful institutions, The Holy Roman Empire.

Not only did I have trouble understanding synchronicity, I also had gaps in my education about any nation or boundary that existed before I was born. For example, I always had this thought, “What was Prussia again?” when I’d encounter it in Wikipedia. And I’d go down the rabbit hole but the way I approached learning was always too focused to retain that information in a larger context.

My goal here is to create a feeling of synchronicity and flow. Synchronicity in that the user can see who was in power at the same time and what world events were unfolding. Flow in that you can click through a nation’s history and see the changing borders, alliances, and dynasties as you move from one ruler to the next.

I hope that you’re able to have fun with this website (and blog post), finding them informative and perhaps even a reference you can come back to later.

Building it

A couple months ago I’d watched Wolf Hall, a miniseries about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. His difficulty in acquiring a divorce made me wonder why some Christian rulers were on the outs with the Pope.

I’d been collecting similar questions for a while:

- What was the Diet of Worms?

- Who were the Jacobites, Orleanists, and Bonapartists?

- What was the relationship between the Gauls and the Celts?

- What is a dauphine, an infanta, a stadtholder, or a prince-elector?

- What happened to these tribes? What is Mercia or Northumbria today? How were Normans different from Anglo-Saxons?

Design

Starting off, I wanted to show a monarch’s basic facts like their name, years active, and house. It should include wars and look the same from the enemy side.

Next, I wanted to show their religion and religious themes, like the Protestant Reformation; also, just themes in general, like chivalry. Finally, I wanted to show events that were transpiring in other parts of the world.

From here, I drafted my earliest mockup:

There would be a modal containing the above information, a timeline for each country, red lines for wars, and a vertical line that tracks your mouse and displays the year.

Technology

I decided to go with d3.js, which you might recognize from the New York Times.

d3 matches data to SVGs. Elements are created dynamically from data and in response to user actions. You can also apply animations, giving your site a responsive feel.

These animations are tied to javascript event handlers, such as mouse hovers and clicks. The syntax for d3 is very intuitive and pleasant to work with.

Feel free to skip ahead if I’m getting too technical, otherwise I’ll walk through a couple features.

Events

The following code sets up filters, allowing the user to focus on events of a particular type.

dateControlContainer.selectAll("circle")

.data(dateControlData)

.enter()

.append("circle")

.attr("cx", function(d, i) { return margin.left + dateControlInterval / 2 + (i * dateControlInterval); })

.attr("cy", height - margin.bottom / 2)

.attr("r", circleRadiusLarge)

.attr("fill", function (d) { return d.color })

.attr("fill-opacity", 0.5)

.attr("class", function(d) { return ['control', d.key].join(' ') })

.on("click", focusDates)

.on("mouseover", function(d) { enlargeCircle.bind(d3.select(this))(this); })

.on("mouseout", function() { reduceCircle.bind(d3.select(this))(this); })

.append("title").text(function(d) { return d.key; });

We start with a previously-created d3 object, a <g> container that we’ve assigned to dateControlContainer. This will hold all of the filters.

We select all SVG <circle> elements in the container (currently zero) and pass in an array of JSON objects, dateControlData, as our data source:

[

{ key: 'philosophy', color: '#FFFFFF' },

{ key: 'science', color: '#000000' },

// ...

]

enter() and append() are directives for what to do with each data element.

attr() will set an HTML attribute - in this case, SVG attributes like x and y. You can set attributes dynamically by passing a function, which is given the data, such as .attr("fill", function(d) { return d.color }).

I like ES6 arrow functions, .attr("fill", d => d.color), for readability but I’m not using a transpiler so I wrote Javascript to ensure compatibility with Internet Explorer.

The .on() function is used to apply event handlers - in this case, click, mouseover, and mouseout. Order doesn’t matter since each line returns the d3 object, making method chaining easy.

The event handlers themselves look like:

function enlargeCircle(el) {

if (detailsOpen) return false

var $this = $(el),

$r = parseFloat($this.attr('r'));

this

.attr("r", $r * 1.25)

.attr("smallR", this.attr("smallR") || $r)

.attr("fill-opacity", 0.75);

}

function reduceCircle(el) {

if (detailsOpen) return false

var $this = $(el),

$r = parseFloat($this.attr('r'));

this

.attr("r", this.attr("smallR"))

.attr("fill-opacity", 0.5)

}

enlargeCircle will transition the circle to be 25% larger and more opaque, while reduceCircle (on mouseout) will return the circle back to its original size and opacity.

Modal

I used two principles for designing the monarch modal.

- Every dimension inherits from the height or width of the browser

- All elements are laid out according to a grid.

The inheritance is nice because the entire website will automagically scale depending on what device you’re using.

My grid system was this: the modal height, divided by 8, is a block. The width would be 5 blocks across, and each element’s width, height, x, and y would be some fraction or multiple of a block.

I sketched it out on paper first because I hate myself.

Using a grid allowed me to easily reason about layout, move elements around, and go from mockup to code.

// House image

timeline.append("image")

.attr("x", detailsX + detailsBlock * 2 - detailsBlockEighth)

.attr("y", detailsY + detailsBlockQuarter + detailsBlockEighth)

.attr("width", detailsBlock / 2)

.attr("height", detailsBlock / 2)

.attr("xlink:href", data.houseImage)

.attr("class", "detail")

The full source code is available on GitHub and comes in around 1,000 lines of code, most of which is d3 (with a little jQuery and Lodash).

Challenges

There were several challenges, first and foremost the sheer amount of time it took to compile all of the data.

On average, each monarch took about 20 minutes:

- pull all relevant details from Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Brittanica

- find a good picture

- create the map

- edit the info to fit into the frame and tell a compelling, accurate story

Sacrifices had to be made: leaving out dates of wars when the text bled into the map, only including the 3 “most important” events, explaining complex intrigue in 100 characters or less… My goal was to be about 95% accurate, leaving Wikipedia for a more accurate detailed view should anything pique the reader’s interest.

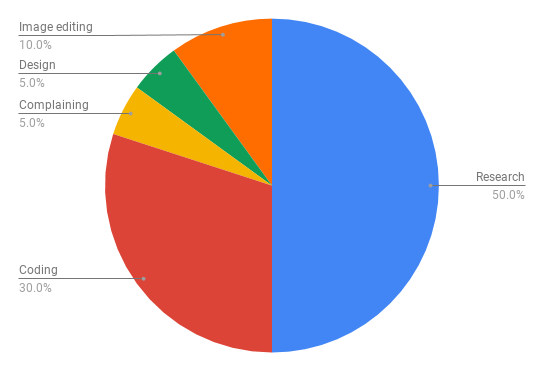

The breakdown of time spent looked something like this.

If I do this again, I’d probably look for an existing dataset and scratch my creative itch by just building out functionality.

Credits

Thanks to my wife for re-designing the details modal. (Hire her.)

Thanks to Chris Barthel, Paul Hayslett, and Eddie Daniels for ideas and creative feedback.

I didn’t keep track of image credits, but they were mostly drawn from Wikimedia Commons.

Map by eddsworldbatboy1, icons by FreePik and Smashicons, and fonts from dafont.com and Google Fonts

Countries

Vassals are usually represented as sovereigns, unless the overlord held the throne like Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and the throne of Spain. Though England was a vassal to France, and Scotland to England, I showed them as sovereign nations.

The map for each monarch represents the extent of their domain as their reign ends; it does not account for succession crises that immediately followed, such as Francia splitting three ways upon the death of Louis the Pious.

Scotland

I started Scotland with the first Dunkeld. There’s a pretty interesting history before that though, including MacBeth, the Picts, and like 20 kings over a couple centuries.

It ends with the ascension of James VI to the English throne, even though Scotland remained an independent country until merging with England to become Great Britain in 1707.

Spain

Starting with Ferdinand and Isabella, Spain was a union of the crowns of Castile, Aragon, and Leon. It wasn’t until the end of the War of the Spanish Succession that Spain became unified under one crown, the King of Spain.

To make things more complicated, after the deaths of Ferdinand and Isabella the Spanish crowns went to their grandson, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. I decided to start with Charles V splitting his empire and passing the Spanish throne to his son Philip.

I was on the fence about including Franco who, besides being a fascist, never styled himself a monarch. He re-established the monarchy, though, and played a critical role in how we understand Spain today. Much moreso than other interregnum leaders, such as Oliver Cromwell.

France

There were kings of the Franks before Charlemagne (the Merovingian line) but French national identity and a “King of France” didn’t come about until much later. Charlemagne, at the height of his power, also controlled what would later be the Holy Roman Empire, Italy, and the low countries. After the death of his son, the land was split three ways.

The western kingdom, West Francia, went to Charles the Bald and closely aligns with modern France. East Francia goes to Louis the German, becoming Germany. Lotharingia, the middle slice which includes Italy, goes to Lothair.

A couple generations later, East Francian king Charles the Fat inherits Lotharingia and West Francia, but things are split 5 ways upon his death.

Obviously, it’s not easy to say what is and is not “France”.

Originally, I wanted to skip Charles the Bald, since he was crowned Emperor of the Romans, instead starting with his son who was not. However that son’s descendant, Charles III, was also crowned Emperor and, for simplicity, I simply opted to start with the founder of the Carolingian dynasty, Pepin the Short.

Arguably the most interesting of modern states, the boundaries of France change perhaps the most dramatically over time from a low-point during the English Angevin Empire

to a high-point during the Napoleonic wars:

Holy Roman Empire

While Charlemagne is the first to be crowned Emperor of the Romans, I decided to start the Holy Roman Empire with Otto I, founder of the Ottonian dynasty. This is largely because there would be overlap with France, as several King of the Franks were also crowned Emperor of the Romans, whereas Otto is the first to be crowned while only holding the lands that will make up the Holy Roman Empire for centuries: modern-day Germany and Northern Italy.

The internal boundaries of the Holy Roman Empire are notoriously complicated.

Germany

Germany on my timeline is not the Germany we recognize today. Since the fall of the Holy Roman Empire, it went from a collection of states to the Confederation of the Rhine, the German Confederation, the North German Confederation, the German Empire, and finally modern Germany.

Throughout this period, Prussia was the most powerful player besides Austria (who is represented separately.) Therefore, in my timeline, “Germany” is a line of the Hohenzollern rulers of Prussia, the North German Confederation, and the German Empire.

Italy

Italy did not exist as we think of it today until 1871, the product of post-Napoleonic visions of Europe and Austrian losses in the Austro-Prussian war.

Before that, the land played host to a plurality of kingdoms and semi-autonomous city-states. Northern Italy was held for a long period by the Holy Roman Empire. A turnstyle of Normans, Angevins, and Habsburgs controlled Sicily. At one point, Sardinia and a kingdom called Two Sicilies held power.

To display a unified Italy would only be four monarchs, starting in 1871 and ending in 1946 after World War II. Since it would add a lot of negative space to the timeline, I left it out.

Terminology

There are a lot of terms involved, some specific to each country. For example, there are a lot of dukes in England, but when someone is called Duke of York they are second in line for succession.

| Term | Meaning | Notes | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prince of Wales | Heir apparent | English | Prince Charles |

| Duke of Rothesay | Heir apparent | Scottish (applies to English since unification) | Prince Charles |

| Prince of Asturias | Heir apparent | Spanish | |

| Infanta | Princess | Spanish, especially eldest daughter who was not heir | |

| Dauphin | Heir apparent | French, used after France acquired the territory of Dauphiné | |

| Archduke | Heir apparent | Holy Roman Empire | Archduke Franz Ferdinand |

| Tsarevich | Heir apparent | Russia | |

| Duke of York | Second in line | England | Prince Andrew |

| Duke of Anjou | Second in line | France | |

| Junior King | Crowned heir apparent | Sporadic practice; French, English, Hungarian | |

| Prince-Elector | Council that elects the Holy Roman Emperor | George I, King of England and Elector of Hanover | |

| Stadtholder | Head of state | Dutch Republic | William of Orange, before becoming King of England |

| Doge | Chief magistrate of Venice or Genoa | Italian | |

| Primogeniture | Hereditary line through the oldest sibling | Salic law | |

| Cadet house | Hereditary line through a younger sibling | Valois is traced back to Capet through second son of Philip III |

Stories

There were so many cool anecdotes that didn’t fit into a timeline, I wanted to share a few of them here.

The Black Dinner

By the 15th century in Scotland, clan Douglas was seen as a powerful threat to the ruling family, Stuart. The Earl of Douglas and his younger brother, both under the age of 17, were invited to dine with the ten-year-old king of Scotland, James II.

While they ate, a black bull’s head, a symbol of death, was brought in and placed before the Earl. The two brothers were then dragged out to Castle Hill, given a mock trial and beheaded.

I think they stole the idea from Game of Thrones, but still pretty baller.

The Pope

In the years since Charlemagne, the relationship between French kings and Holy Roman Emperors and the Popes was mixed. At certain points, the Emperors saw themselves as defenders of Christianity with the Pope subservient to them, while France was seen as the defender of the papacy against the greedy Empire. Go forward or backwards a hundred years and you could probably switch those around.

Vying for influence in Rome, both the Empire and France supported various competitors, known as antipopes. Often, these were German or French bishops or just friendly to their side of the rivalry.

In 1309, France forced the election of a French pope, Clement V. Refusing to return to Rome, he moved his court to the fortress of Avignon. After seven popes in Avignon, the See was moved back to Rome where the Western Schism broke out between French and Pisan factions.

The French faction was supported by France, Spain, and Scotland. The Pisan faction was supported by just about everyone else. And, to make things more complicated, by 1410 a third claimant had been put forth.

All three excommunicated each other but, being popes, they were immune.

The French line was declared invalid, the Pisans claimed victory, and enough people were left angry at the papacy that the groundwork was laid for the Protestant Reformation.

Disputed Kings of France

The first Norman king of England, William the Conquerer, was a vassal to the King of France through his status as Duke of Normandy. Through continental holdings (Normandy, Aquitaine, Maine, Anjou) his descendants remained French vassals for the next 300 years.

In 1294, France invaded Gascony, held by England, and then Aquitaine. When the last French Capetian king died without heir, the English king Edward III had a claim to the throne and pressed it on the urging of dissatisfied French nobles, causing the start of the Hundred Years’ War.

France, now ruled by the house of Valois, suffered disastrous early defeats and signed the Treaty of Calais, giving all of southwestern France to England. Within 10 years, France under Charles V had recovered and through military victories reclaimed the land it had lost.

Charles VI took power but, at the age of 24, went insane and the power of the throne weakened. Power in France was thus split between the dukes of Burgundy and Orleans, the latter of whom sided with English Henry V, prompting a renewed invasion.

After an English victory at Agincourt, Charles VI signed the Treaty of Troyes, marrying his daughter to Henry V and giving the English king succession to the French throne over his son, the dauphin. France was split, with the northern half supporting England and the southern half remaining loyal to the dauphin, Charles VII.

Henry V died a month before the French throne went vacant, whereupon Henry VI, a minor, was crowned at Paris in 1422. In the south of France, inheriting a desperate cause, Charles VII rallied support with Joan of Arc, lifting the English seige of Orleans and crowning himself king in Reims in 1429.

By the time Henry VI came of age, Charles VII had made peace with Burgundy and gained momentum, retaking Paris, then Normandy and finally Bordeaux in 1453, ending the Hundred Years’ War.

Religion

As a non-Christian, I’ll be the first to say I don’t fully appreciate the difference between Catholics and Protestants. But Europeans of the 16th and 17th century sure did.

Spain felt so strongly about it that they sent an armada to England. France killed 3,000 Protestants in Paris in a single day. The Holy Roman Empire lost over 7 million citizens fighting the Thirty Years’ War over it.

England, after two Catholic regressions in the form of Mary I and James II, passed a law excluding Catholics from ever holding the crown again. After Anne died, there were 57 people passed over in the line of succession, giving the crown to a Protestant elector in a very Catholic, but very neutered, Empire.

I can’t personally imagine turning down a chance to rule one of the most powerful countries on Earth because I thought the Pope speaks to God, but I also live in the future where you don’t get burned at the stake for saying Jesus was crucified with three nails instead of four.

But some people felt like I do, like the Good King Henry of France. A Protestant by birth, as King of Navarre he led the French Huguenot cause against the Holy League, a papal alliance formed because the Catholic King of France, who just finished killing 3,000 Huguenots, wasn’t taking this whole Protestant thing seriously enough.

In order to inherit the French crown, ever the pragmatist, Henry converted and that was that. Of course he was later assassinated, but that’s neither here nor there.

Names

Whether it was Denmark alternating back and forth between Frederick and Christian for 459 years, or Prussia unaware that names exist outside of William and Frederick, there seemed to be a paucity of original names.

Here are 8 sequential French kings, starting with Charlemagne (Charles the Great):

Come on, Lothair. Get with the program.

To circumvent this, leaders were usually given an epithet. Some were pretty nice, like Charles the Great and Louis the Pious.

Some were okay, like William the Silent or Aethelred the Unready.

But honestly, some were pretty rude.

| the |

Fashion

While testing my website, I noticed something. Even though they were continually at war, every Western European monarch followed the same fashion trends.

Around the year 1500, everyone was really into hats.

100 years later, frills were big.

And finally, 100 years after that, it was wigs.

Toss in a pair of stilletos and you’ve reached peak masculinity. It’s been all downhill since.

Inbreeding

Hoping to keep the door open for Austrian Succession to the Spanish throne, the Austrian Habsburgs kept marrying their daughters to Spanish Habsburgs.

After generations of this practice, Charles II of Spain was completely bald, senile, and sterile. At the time of his death at 38, the autopsy found “his heart was the size of a peppercorn, his lungs corroded, and he had a single testicle, black as coal.”

This is his family tree:

Circles are bad. You want to avoid circles.

With no heirs and tired of Austrian Habsburg influence in his court, he named the French Bourbon Philip V as his heir, sparking off the War of Spanish Succession. This war would result in the end of Habsburg rule over the Netherlands and the elevation of Prussia to a kingdom.

Paintings

I developed an appreciation for the Neoclassical portraitists - all of the contemporary-looking portraits of ancient kings on my website. Louis-Felix Amiel, Georges Rouget, and Merry-Joseph Blondel created historical paintings that deepened my own desire to learn.

Here are a few non-portraits I’d saved that capture important historical events:

Siege of Paris, Jean-Victor Schnetz, c. 1837

Odo, the Count of Paris, defends the city against Danish Vikings led by Rollo in 885. He is later crowned King of West Francia, deposing the unpopular Charles the Fat.

Coronation of Charlemagne, Friedrich Kaulbach, 1861

Seeking to fill a vacancy in power, Pope Leo III, crowns Charlemagne Emperor of the Romans for his role in defeating the Hungarian invasion.

Liberty Leading the People, Eugene Delacroix, 1830

Tired of Charles X and his support for ultra-royalist religious factions, he is overthrown and replaced with Louis-Philipe I. I’d always thought this was a painting of the French Revolution.

Recommendations

If you’re interested in something to watch, I found the following to all be interesting

- Wolf Hall (Hulu)

- The Favourite

- The Lion in Winter

- The Crown (Netflix)

- BazBattles

And perhaps the coolest video, which I used to create the maps:

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this post! If there’s anything you’d like to see included, or you want to reach me, shoot me an email or reach out via the social links on the left.

Thanks for reading!